“No Stress”: Sad Truth Behind The Popular Motto

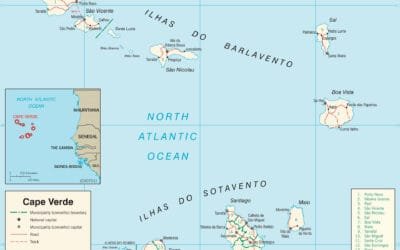

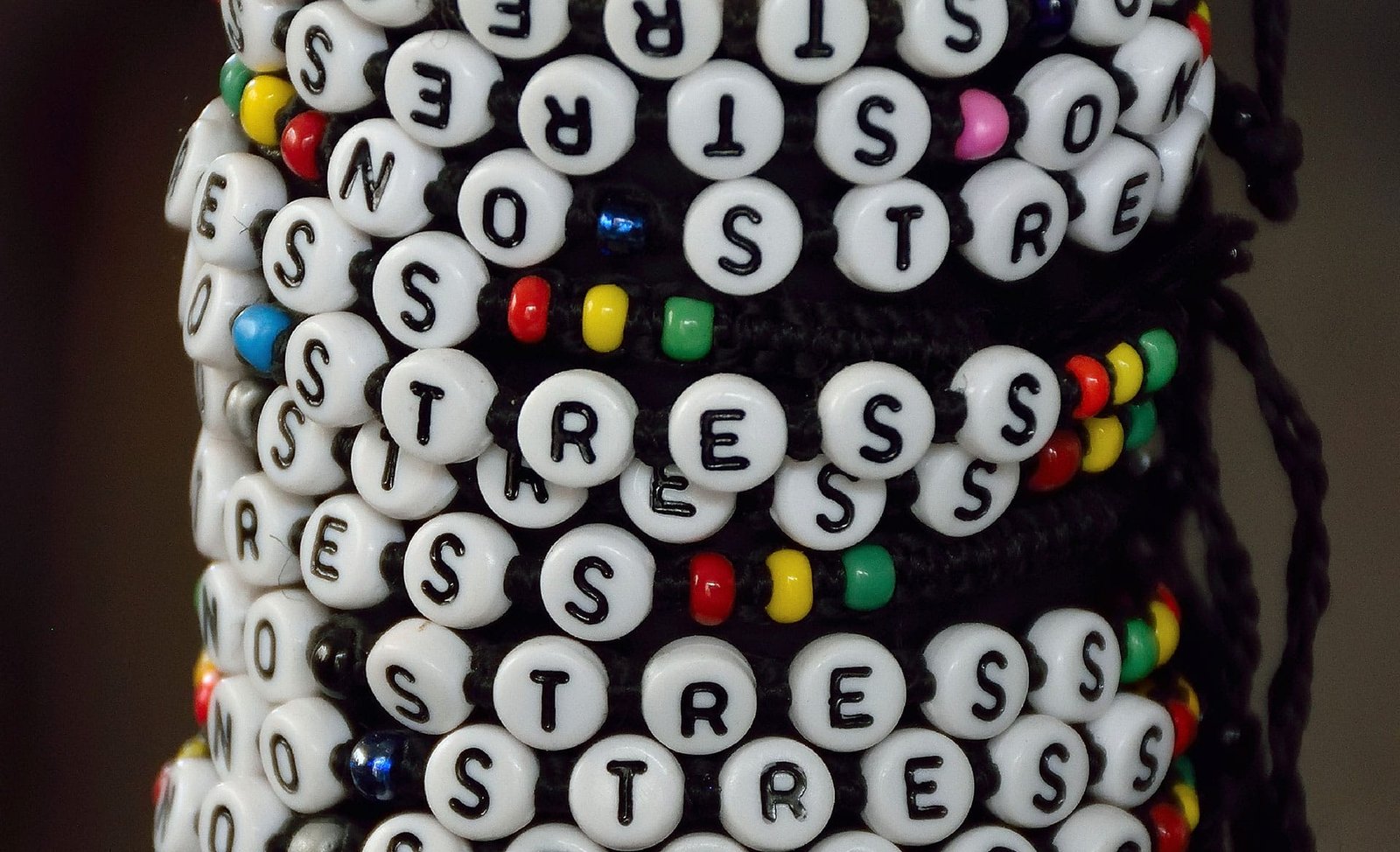

Cape Verde, and particularly its most visited islands — Sal and Boa Vista — has in recent years become inseparable from a phrase familiar to nearly every traveller who passes through: No stress. Arriving at Amílcar Cabral International Airport, visitors encounter it almost immediately — printed on caps, bracelets, souvenir t-shirts, welcome signs, and travel brochures. It echoes from the voices of hotel staff, tour guides, and beach hawkers, often delivered with a smile and a soft handshake.

To the first-time tourist, it seems more than a slogan. It feels like a cultural truth — a kind of mantra that reflects the spirit of the islands. No stress, say the locals, and visitors quickly believe it. But look closer, and a more complex picture emerges: one that has less to do with timeless tradition and more to do with the dynamics of a rapidly built tourist economy.

No Stress: A Slogan Born of Salesmanship

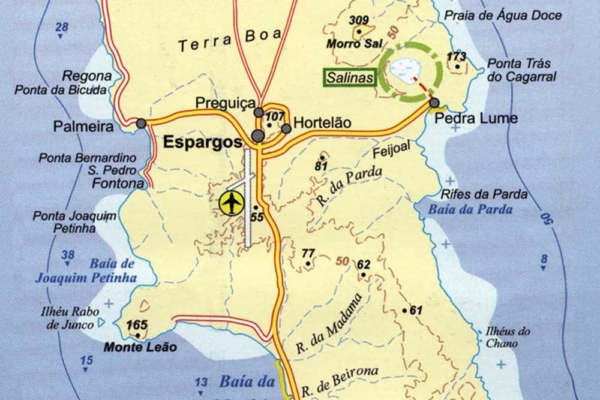

“No stress” is not a phrase with deep historical roots in Cape Verdean society. Its rise coincides almost precisely with the islands’ turn towards mass tourism — a shift that began in the early 2000s, centred around the resort town of Santa Maria in southern Sal. Until then, Sal was a sparsely populated area, known for its barren landscape, salt flats, and strong winds. Cultural life, in the more profound sense, belonged more to other islands in the archipelago.

As the hotels increased, so did the number of people arriving in search of work — many from other Cape Verdean islands, while others came from West African countries, especially Senegal. With them came a wave of informal trade: carvings, jewellery, fabrics, and trinkets — often imported, rarely local. Vendors introduced a style of beachside commerce tailored for European tourists: polite, persistent, and well-rehearsed. Central to this script was a phrase that put tourists at ease: No stress.

It was friendly. It was vague. It worked.

How It All Started

The words became a soft entry into a sales pitch: “Hello, my friend. Where are you from? No stress. Just one question…” For cautious tourists unused to being approached on a beach, it was a disarming start. The slogan stuck. In time, it spread — from one vendor to the next, and then beyond the beaches, into the broader language of tourism on the island.

Soon, no stress was printed on everything from travel brochures to airport souvenirs. Tour guides adopted it. Hotel entertainers parroted it. What began as a tool of persuasion had become a national brand. Tourists carried the phrase home like a keepsake, repeating it as proof of their relaxed island escape.

What Gets Lost: Morabeza

However, as the slogan gained popularity, it began to overshadow something far older and more authentic: morabeza. Morabeza is a Creole concept that lacks a precise English translation. It embodies warmth, hospitality, gentleness, and a way of life deeply woven into Cape Verdean society. It is not performed — it is lived. One sees it in how neighbours share food, how strangers are greeted with kindness, how music and conversation fill long evenings without any sense of rush.

Unlike “no stress,” morabeza resists branding. It doesn’t fit neatly on a keychain. It doesn’t start a sales pitch. It cannot be taught in a crash course to hotel staff. But it is real — and still present in quieter parts of the country, away from the resorts.

Behind the Smiles: The Economics of the “No Stress” Phrase

The story of no stress is not just about marketing. It also reveals the hidden pressures of life in the tourism sector. Many people who repeat the phrase dozens of times a day live with considerable economic stress. They are often informal workers, many of whom are undocumented, operating under the shadow of seasonal tourism, low earnings, and occasional police crackdowns. A field study in Boa Vista noted how “no stress” signs were placed in shop windows not as declarations of mood, but as shields — pre-emptive defences against complaints from uneasy tourists.

For some vendors, the phrase became a survival strategy. One researcher called it “a mask that conceals anxious daily lives.” What tourists heard as cheerfulness was often, in truth, a performance shaped by economic need.

Illegal Sellers Arrested

In 2009, Senegalese authorities arrested over 30 unlicensed beach vendors — the majority of whom were Senegalese — accused of bothering tourists. Though such events rarely make the news, they expose underlying tensions. Locals sometimes voice frustration that these vendors, often selling goods produced elsewhere, distort perceptions of Cape Verdean culture. On travel forums, some tourists complain that “no stress” can become a prelude to stress, particularly when persistent sales tactics cross a line.

The Limits of a Catchphrase

Travel to less-visited islands — Fogo, Santo Antão, São Nicolau — and the difference is immediately noticeable. No one greets you with no stress. There are no beach hawkers. There is no street-level tourism industry built around souvenir sales. What remains is something quieter, more sincere, and more challenging to package. The slogan simply doesn’t exist there.

This contrast is telling. It confirms that no stress emerges from Cape Verde as a whole, but rather from the specific conditions of Sal and Boa Vista — places that have been rapidly and intensely shaped by tourism, where economic opportunity depends on satisfying foreign expectations.

In less than two decades, a phrase once used to make a sale became a brand that now shapes the outside world’s image of Cape Verde. It appears on YouTube travel vlogs, football jerseys, and café menus. It is quoted in travel articles and embedded in package holiday slogans. And in becoming a symbol, it has edged out more profound truths, among them the subtle, lived reality of morabeza.

“No Stress”: Culture or Branding?

The story of no stress is not one of deception, but of commercial transformation. Like many tourism slogans around the world, it took a loosely authentic sentiment — a general friendliness, a laid-back pace — and turned it into a consumable narrative. That narrative, repeated often enough, began to look like the truth.

Not all that is marketed as culture is culture. Sometimes it is branding. And sometimes, good branding can overshadow the more meaningful, less visible aspects of life that were there long before the souvenir stalls and package deals.

Biography

- Wilson Semedo Martins, Márcio Martins, and Elisabete Paulo Morais, Exploring the Influence of Social Media on Tourist Decision-Making: Insights from Cape Verde, Tourism and Hospitality, 2025;

- A Framework on Eudaimonic Well‑Being in Destination Competitiveness: Cape Verde, Tourism and Hospitality, 2025;

- Constructing Self‑Reliance through Morabeza in Island Networks, Doshisha University research

- Bordonaro, Lorenzo. “No Stress in Cape Verde: Economic Strategies, Migration and Tourism in Sal Island”, 2014, Cahiers d’Études Africaines.

- Godwin Ariguzo, Leopold Lessassy, D. Steven White, Resort Tourism and Sustainable Economic Development: The Italian Experience in Cape Verde, SSRN (April 1, 2004);

- Carvalho, João; Barbieri, Carla. “Tourism, culture and authenticity in small island destinations”, 2021.

- Interviews with local traders and observations in Santa Maria (2018–2023).