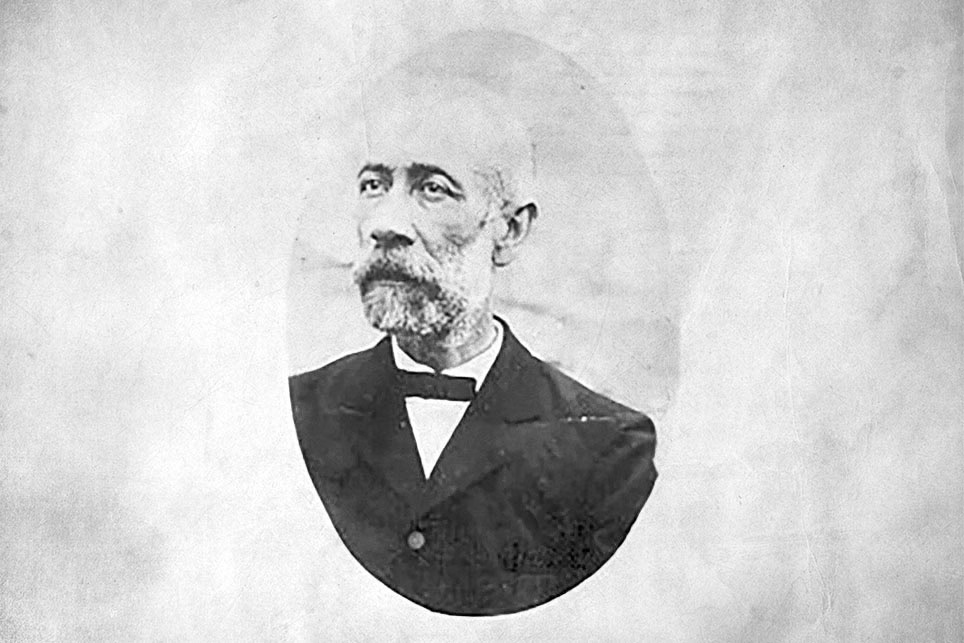

Manuel António Martins: The Napoleon of Cabo Verde

Manuel António Martins: From a Sailor to a Salt Magnate

Manuel António Martins was born in 1772 in Braga, northern Portugal. In 1792, as a 21-year-old aboard the Portuguese sloop Sumaca, a storm near the Canary Islands pushed his ship off course, eventually leading him to the Cape Verde archipelago. Rather than return to Europe, Martins seized the opportunity — along with the cargo of wine on board — and stayed. This calculated move set him on the path to becoming one of the most powerful colonial figures in the Atlantic islands.

Martins quickly turned his attention to Sal Island, which was largely undeveloped at the time. He recognised the economic potential of Pedra de Lume’s salt pans and began developing salt extraction there in the mid-1790s. In 1804, he commissioned a 600-metre tunnel to access the crater, laying down iron rails and carts to transport salt efficiently. He also constructed a pier to improve maritime access.

To support this growing enterprise, he founded the village of Pedra de Lume. Enslaved workers initially supplied labour. In the 1830s, Martins established Santa Maria on the island’s southern coast as an additional export point. By the mid-19th century, Sal alone was exporting more than 30,000 tonnes of salt annually, supplying markets in Brazil and West Africa. Martins had turned a barren volcanic island into one of the region’s major export hubs.

Commerce and Consolidation of Power

Manuel António Martins didn’t limit himself to salt. He expanded into fish, livestock, hides, and cotton, operating across Boa Vista, São Nicolau, and São Vicente. His economic reach spanned much of the archipelago. In 1805, he was appointed administrator of Sal. Just three years later, he was granted the right to collect customs revenues — a privilege rarely granted to private individuals.

Strategic family ties underpinned his rise to power. He married Maria Josefa Ferreira, daughter of the Boa Vista commandant Aniceto António Ferreira. Their sixteen children strengthened his influence across both business and government. Martins became a central node in a network of power that blended private capital with colonial administration.

In 1819, U.S. Consul Samuel Hodges Jr. appointed Martins as vice-consul for the United States on Boa Vista. The role gave him legal cover and expanded his access to international shipping routes. American ships on transatlantic voyages regularly stopped in Cape Verdean ports. As vice-consul, Martins was positioned to issue documents and facilitate trade — both legal and otherwise.

He invested heavily in infrastructure. Manuel António Martins built paved canals to bring freshwater to settlements, supported shipyards, and expanded warehouse facilities. His model, which combines entrepreneurship with public function, earned him a unique reputation. He was not merely a merchant; he was becoming a colonial institution in his own right.

Manuel António Martins’ Political Ambition

Initially, Martins worked closely with Governor António Pusich, who governed the islands from 1818 to 1822. Together, they launched a tuna export venture. However, tension grew as Martins’ wealth and independence increasingly rivalled that of the colonial authority.

In 1820, accusations surfaced that Martins planned to cede control of Sal and São Vicente to British commercial agents. Though likely politically motivated, the rumours fuelled suspicion and unrest. In 1821, Martins backed a civic uprising in Praia that ousted Pusich and established a provisional junta. The civilian government lasted until 1823, highlighting Martins’s ability to shape not just commerce but politics.

His rise peaked in 1833, when Portugal’s liberal regime appointed him civil prefect of the Cape Verde Islands and Portuguese Guinea. The position gave him sweeping authority over both islands and mainland territories. He reorganised municipal boundaries, establishing the municipality of Santa Catarina on Santiago Island. However, the role was abolished in 1835 amid political pushback from Lisbon.

Despite losing the title, Martins remained a dominant figure in Cabo Verdean public life until he died in 1845. His political manoeuvres made him a de facto ruler — one whose authority was recognised even when official titles were stripped away.

Salt, Slaves, and Controversy

Martins’ industrial achievements are inseparable from his role in the slave trade. Though Portugal banned transatlantic slavery in 1836, enforcement was lax, and illegal trafficking continued through Cape Verdean ports.

As a wealthy trader, customs officer, and U.S. vice-consul, Martins had the authority to issue ship registrations. These documents, often falsified, allowed slavers to evade British anti-slavery patrols. His commercial empire provided logistical support to slavers who resupplied, refitted, or hid among legitimate merchants.

Enslaved Africans were employed in his salt pans and infrastructure projects. Some records suggest Martins operated holding facilities for enslaved people awaiting shipment. His network extended across Portuguese and British shipping routes, making him a central figure in sustaining the illegal trade.

While Martins modernised Sal’s economy, he did so on the backs of trafficked labour. His status as a “builder of industry” is complicated by his deep involvement in one of history’s greatest injustices. This contradiction has fuelled debate about his legacy, especially as Cape Verde re-evaluates its colonial past.

Manuel António Martins: Legacy in Stone, Salt, and Memory

Martins died on 6 July 1845 in Pedra de Lume, the village he built. His descendants remained influential, and the infrastructure he left behind — salt pans, tunnels, canals, and early rail — is still visible today.

Santa Maria, now one of Cape Verde’s top tourist destinations, began as a salt-export village founded by Martins. His economic blueprint — focused on transport links and port access — still shapes the geography and development of Sal Island. Yet monuments to Martins are rare. His story is taught selectively, and public commemoration remains muted.

Some view him as a visionary, an entrepreneur who modernised a remote outpost. Others see a profiteer who built his empire through exploitation and slave labour. As Cape Verde wrestles with how to remember its colonial figures, Martins remains a symbol of both ambition and brutality.

His title, “Napoleon of the Islands,” reflects this complexity. Like Napoleon, he left a lasting legacy built through calculated ambition and political manipulation. And like Napoleon, he invites admiration and critique in equal measure.

Bibliography

- Manuel Antonio Martins: Napoleon of the islands on Cape Verde History Unearthed blog;

- Western Africa and Cabo Verde, 1790s-1830s: Symbiosis of Slave and Legitimate Trades by G.E. Brooks.

- Cabo Verde Terra de Morabeza: Uma Viagem Atraves de Sua Historia e Cultura by Faria, Luis António, Suzana Abreu, and Américo C. Araújo, Valrico: LAF Enterprises, 2012;

- Manuel António Martins on Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia;