Amílcar Cabral: The Agronomist Who Cultivated Revolution

The Seeds of Liberation: How a Cape Verdean Agricultural Engineer Became Africa’s Most Influential Revolutionary Theorist

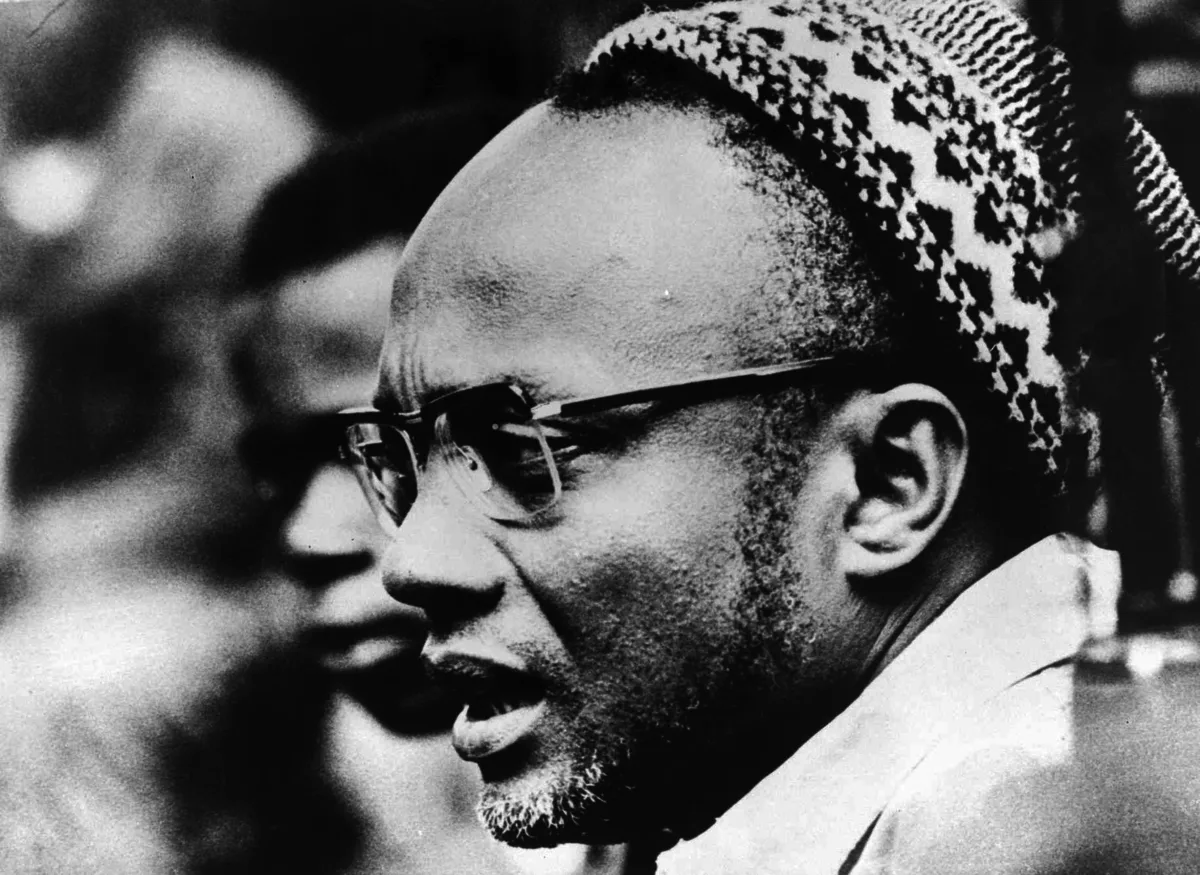

On a humid January evening in 1973, Amílcar Cabral stepped out of his car near the PAIGC headquarters in Conakry, Guinea. Within moments, the 48-year-old revolutionary leader lay dying, shot by members of his own party—a tragic end to one of the twentieth century’s most original anti-colonial thinkers. Eight months later, Guinea-Bissau would declare independence from Portugal, vindicating the struggle Cabral had led but would never see completed.

Yet, to understand Cabral solely as a martyr of African independence is to miss the remarkable originality of his contributions to revolutionary thought. He was an agronomist who mapped soil erosion patterns while, at the same time, charting paths to liberation. He’s a poet who wielded statistical analysis as deftly as verse, and a Marxist theoretician who insisted that “culture was key to national liberation”. In an era when anti-colonial movements often imported wholesale ideologies from Moscow or Beijing, Cabral demanded something different: a return to the source, a revolutionary practice rooted in African reality.

Between Two Worlds

Amílcar Lopes Cabral was born on September 12, 1924, in Bafatá, Portuguese Guinea, to Cape Verdean parents. From the earliest years of his life, he became familiar with the complex colonial hierarchies that he would spend his life dismantling. His father, Juvenal, was a schoolteacher; his mother, Iva Pinhel Évora, worked variously as a seamstress and hotel cook. When Amílcar was eight, the family returned to Cape Verde, where the boy would come of age during one of the archipelago’s periodic catastrophes.

The drought of the 1940s killed between 50,000 and 60,000 people — nearly a third of Cape Verde’s population. For the young Cabral, witnessing children his age dying of starvation while Portuguese colonial ships exported what little food remained became an important lesson in political education. He would later recall:

“We watched the people die, and we understood that colonialism was not an abstract concept.”

This double belonging — to both Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde — would profoundly shape Cabral’s revolutionary vision. Cape Verdeans were regarded as “civilised” because they spoke Portuguese, were of the Christian faith, and adopted Western dress. It gave them an intermediate position in the colonial hierarchy, somewhere between Portuguese settlers and mainland Africans. Yet this privilege was precarious, built on a foundation of manufactured division that Cabral would later identify as one of colonialism’s primary weapons.

The Making of a Revolutionary Scientist

When Cabral arrived in Lisbon in 1945 on an agronomy scholarship, he entered not just a university but a crucible of African nationalist thought. At the Casa dos Estudantes do Império — the House of Students from the Empire, as Portugal euphemistically called its colonies — Cabral encountered fellow students who would become leaders of liberation movements across Lusophone Africa: Agostinho Neto from Angola, Marcelino dos Santos from Mozambique, and Mário de Andrade from São Tomé.

Together, they formed secret study groups, where they read banned texts and started developing the intellectual framework for decolonisation. The influence of Négritude writers, such as Léopold Sédar Senghor and Aimé Césaire, was profound.

“Wonderful poems written by blacks …, poems that speak about Africa, slaves, men, life and men’s aspirations.”

Cabral wrote of this period, when he began to conceive of himself not as Portuguese or even Cape Verdean, but as African.

Yet unlike many of his contemporaries, Cabral chose to pursue agricultural engineering rather than law or medicine. This decision reflected both practical calculation — Portugal desperately needed agronomists for its colonies — and revolutionary foresight. He’d say:

“To know the land is to know the people who work it.”

Walking 60,000 Kilometres to Revolution

Returning to Guinea-Bissau in 1952 as an agricultural engineer for the colonial government, Cabral undertook what appeared to be a routine bureaucratic task: conducting an agrarian census for the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation. From late 1953 to April 1954, he travelled more than 60,000 kilometres, collecting data from approximately 2,248 peasants.

But this census was anything but routine. As Cabral travelled through the villages of Guinea-Bissau, he mapped the terrain for guerrilla warfare. Notably, he identified potential allies and developed a deep understanding of local conditions. All that would prove crucial to the liberation struggle. He studied not just crop yields, but also social structures, not just soil types, but the grievances of those who worked the soil.

The census revealed to Cabral the contradictions of Portuguese colonialism. Colonial propaganda portrayed Portugal’s African territories as integral provinces of a multiracial empire. At the same time, Cabral’s data told an utterly different story of systematic exploitation, forced labour disguised as “contract work,” and an economy structured entirely around extraction.

“For him, the census was not only a set of tables and numbers, but also the possibility to read, comprehend and act on the prevailing agricultural dynamic”.

From Peaceful Protest to Armed Struggle

On September 19, 1956, during a clandestine visit to Bissau, Cabral and five others founded the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC). Initially, the party pursued a strategy of peaceful resistance, organising among urban workers and dock labourers in Bissau.

This approach came to a violent end on August 3, 1959. Dock workers at the Port of Bissau’s Pijiguiti docks went on strike for higher pay, but a manager called the Portuguese state police (PIDE), who shot into the crowd, killing at least 25 people. The Pidjiguiti Massacre, as it became known, transformed the liberation movement. Cabral later reflected:

“We learned that against Portuguese fascism, against colonialism, we could not expect to achieve anything through peaceful means.”

The PAIGC shifted its focus to the countryside, where Cabral’s agricultural census proved invaluable. He knew which ethnic groups controlled which territories, understood seasonal agricultural patterns that would affect guerrilla operations, and had established contacts with village elders throughout the country. By 1963, the armed struggle had begun in earnest.

The Weapon of Theory

What distinguished Cabral from many contemporaries was his insistence that revolutionary practice required revolutionary theory — but theory grounded in concrete African realities rather than imported dogma. In his famous 1966 address to the Tricontinental Conference in Havana, “The Weapon of Theory,” Cabral argued that:

“The struggle against our own weaknesses… is the most difficult of all, whether for the present or the future of our peoples”.

This self-critical approach extended to his analysis of class and revolution in Africa. While orthodox Marxism identified the industrial proletariat as the revolutionary class, Cabral recognised that in Guinea-Bissau, as in most of Africa, peasants would be the primary agents of change. But he also understood that the petite bourgeoisie — educated Africans like himself who had benefited from colonial education — had a crucial role to play, provided they could undergo what he called “class suicide,” renouncing their privileges to merge with the masses.

Central to Cabral’s revolutionary theory was his concept of “re-Africanization.” He articulated a process of “re-Africanization,” by which Africa’s elite, long beholden to the colonisers for their education and employment, would re-embrace indigenous African culture and reintegrate themselves into mass popular culture. This wasn’t romantic nostalgia for a pre-colonial past but a dialectical process through which colonised peoples would reclaim their capacity to decide about themselves and make history. Cabral argued that:

“Culture is simultaneously the fruit of a people’s history and a determinant of history.” Colonial domination could only be maintained through “the permanent and organised repression of the cultural life of the people”.

Therefore, cultural resistance was inseparable from political and military resistance.

Building Liberation in Liberated Zones

As PAIGC forces gained control of rural areas, Cabral insisted that liberation meant more than military victory. In the liberated zones, the party established schools, hospitals, and people’s stores that sold goods at prices lower than those of colonial merchants. As an agronomist, he trained his troops to teach local farmers better farming techniques, ensuring they could increase productivity and feed their own families and communities.

The focus on concrete improvements to local everyday life showed Cabral’s great understanding of that:

“People are not fighting for ideas, for things that are in anyone’s head. They are fighting for material benefits, to live better and in peace, to see their lives progress, to secure the future of their children”.

The Revolution wasn’t an abstract ideological project, but a response to immediate human needs.

The liberated zones became laboratories for the society that the PAIGC planned and envisioned. Democratic assemblies let villagers make decisions collectively. In schools, children learned in local languages before Portuguese, and health clinics provided care regardless of one’s ability to pay. By 1972, PAIGC controlled two-thirds of Guinea-Bissau’s territory and had established functioning governmental structures in these areas.

Racing Against Time

Here’s what keeps researchers awake: The Cape Verde population teeters on the edge of genetic viability. Three hundred individuals isn’t just a small number — it’s a bottleneck that poses a significant threat to long-term survival. Every whale that doesn’t return from migration represents a measurable loss to genetic diversity.

Commercial whaling drove this population to the brink of extinction. Between 1866 and 1966, an estimated 200,000 humpback whales were killed globally by hunters. Cape Verde’s population bore its share of slaughter. What swims here now are descendants of the few that escaped the harpoons.

Modern threats are subtler but no less deadly. Ship strikes and stress factors increase as maritime traffic grows. Ocean acidification, driven by the absorption of carbon, affects the entire food chain. Microplastics accumulate in whale tissues. Climate change shifts ocean currents, which disrupts the conditions that have made Cape Verdean waters suitable for humpback breeding across millennia.

The recent discovery in West Greenland adds another concern. Greenland maintains a legal subsistence hunt for humpback whales, with an annual quota of ten whales. If Cape Verde whales regularly travel there, even a single whale taken could represent a significant loss to the breeding population.

The Double Death

Cabral’s assassination on January 20, 1973, by members of his own party remains controversial. The assassins were Guineans who resented what they perceived as Cape Verdean dominance within PAIGC leadership — a tragic manifestation of the ethnic divisions that colonialism had cultivated and that Cabral had spent his life trying to overcome.

He was killed by Guineans who felt that Cape Verdeans had too much ascendancy in the PAIGC. His death reflected the profound challenge of building unity across the divisions colonialism had created and reinforced over centuries. Even within the liberation movement, the poison of ethnic antagonism proved difficult to purge entirely.

Yet Cabral’s vision survived his death. On September 24, 1973, PAIGC unilaterally declared Guinea-Bissau’s independence. The following year, the Carnation Revolution in Portugal — partly triggered by the costs of colonial wars — brought down the fascist regime, leading to the independence of all Portuguese African colonies. Cape Verde achieved independence in 1975, with many members of the PAIGC forming its first government.

The Unfinished Revolution

Today, both Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde face challenges that, most likely, wouldn’t surprise Cabral. Guinea-Bissau has experienced chronic political instability, with the military frequently intervening in politics. Cape Verde, while much more stable, remains economically dependent on remittances and foreign aid. The dream of unity between the two nations ended in 1980 when a coup in Guinea-Bissau removed Cabral’s half-brother, Luís, from power — what some called Amílcar’s “second death.”

Yet Cabral’s intellectual legacy extends far beyond the nations he helped liberate. His writings on culture and national liberation had a profound influence on revolutionary movements across Nicaragua to South Africa. He insisted that theory must emerge from good analysis rather than from dogmatic application of foreign models. And by that, anticipated later critiques of development economics. His concept of “class suicide” challenged both Marxist orthodoxy and nationalist romanticism.

Perhaps the most important is the fact that Cabral demonstrated that revolutionary leadership could be simultaneously militant and humanistic, scientifically rigorous and culturally grounded, international in scope, yet rooted in local realities. In an era of algorithmic thinking and technocratic solutions, his integration of agronomy and revolution, statistics and poetry, offers a model of engaged intellectualism that remains urgently relevant.

The Revolutionary as Teacher

“Tell no lies, claim no easy victories.”

Cabral instructed PAIGC militants in 1965 — advice that captured his commitment to revolutionary honesty. He understood that a proper, sustainable transformation required not just seizing power but fundamentally changing consciousness. He saw it in not just defeating Portuguese colonialism but overcoming the internalised hierarchies it had created.

In his final New Year’s message, delivered days before his death, Cabral spoke of the challenges ahead with characteristic clarity:

“The struggle continues, more difficult perhaps than the armed struggle, the struggle to build, to create a new society, a new mentality, a new kind of African.”

Cabral never claimed to have all the answers. What he offered instead was a method: concrete analysis of concrete conditions, respect for popular knowledge, integration of theory and practice, and above all, confidence in ordinary people’s capacity to transform their own lives.

“Our people are our mountains.”

He said, adapting Mao’s famous phrase to Guinea-Bissau’s flat terrain — but also asserting that revolutionary strength came not from geography but from human solidarity.

Legacy of the Practical Dreamer

Fifty years after his assassination, Amílcar Cabral remains one of the twentieth century’s most important revolutionary thinkers, though he is less known than contemporaries like Che Guevara or Frantz Fanon. He was voted the second-greatest leader in the world in a poll conducted by BBC World History Magazine in March 2020. Yet, his works remain largely untranslated, and his contributions to revolutionary theory are underappreciated.

This obscurity is perhaps fitting for someone who warned against personality cults and insisted that individuals don’t make history — people do. Yet, in our current moment of rising authoritarianism, ecological crisis, and persistent colonial legacies, we could really get some vital lessons from Cabral’s integration of environmental science and liberation politics, as well as his attention to culture as a site of struggle, and his insistence on grounding revolutionary practice in careful study of local conditions. Fanon wrote:

“The colonised man who writes for his people ought to use the past with the intention of opening the future.”

Cabral did precisely this, mining African traditions not for museum pieces but for tools of transformation. His revolution was unfinished, his vision unrealised, but the seeds he planted — literal and metaphorical — continue to germinate in unexpected places.

Ultimately, Cabral’s life exemplifies a great stand against a very universal challenge that extends far beyond the specifics of Portuguese colonialism or even African liberation. He raises important questions:

- How do we construct movements that are both deeply rooted and internationally connected?

- How do we develop theories adequate to our concrete realities while learning from global struggles?

- How do we create unity across differences without erasing that difference?

These questions have no easy answers. However, as Cabral taught, the point is not to have all the answers, but to keep asking better questions, always grounded in the struggles and aspirations of ordinary people. He insisted that:

“No one can free another. People free themselves.”

The task of revolutionary leadership is simply to create conditions where that self-liberation becomes possible.

For Cabral, revolution was ultimately an act of love — love for the people, love for the land, and love for the possibility of human beings transcending the circumstances of their oppression. It was this love, disciplined by scientific analysis and strategic thinking, that enabled him to see in Guinea-Bissau’s eroded soils not just an agricultural crisis but revolutionary potential, to find in Cape Verde’s drought-stricken islands not just tragedy but the seeds of transformation.

The mountains he spoke of were never geographical. They were the accumulated strength of people who refused to accept that history is something that happens to them rather than something they make. In this sense, Cabral’s revolution continues wherever people gather to study their conditions, organise for change, and insist — against all evidence to the contrary — that another world remains possible.

Bibliography & Further Reading

- Amílcar Lopes Cabral – Biography, Charles Peterson, Encyclopedia Britannica;

- The Weapon of Theory, Amilcar Cabral (1966), Marxist Writers’ Archive;

- Amílcar Cabral The Life of a Reluctant Nationalist (book), António Tomás, Hurst;

- Amílcar Cabral’s life, legacy and reluctant nationalism – an interview with António Tomás, ROAPE, Review of African Political Economy;

- The Socialist Agronomist Who Helped End Portuguese Colonialism – An interview with Peter Karibe Mendy, Sa’eed Husaini, Jacobin, 2019;

- Cabral: A Revolutionary of Double Belonging: The Ninth Pan-Africa Newsletter (2024), Tricontinental Institute of Social Research;

- Amilcar Cabral and the Liberation Struggle, Sónia Vaz Borges, The People’s Forum, 2020;

- Cabo Verde: Reimagining the biography of Amílcar Cabral, Dulce Araújo, The Vatican News, 2023;

- Revolutionary Cut Short Amílcar Cabral, global figure in anticolonialism, Toby Green, History Today, 2021;

- Amílcar Cabral – African Marxist liberation leader – murdered 50 years ago by agents of Portuguese colonialism, Carlos Lopes Pereira, Mundo Obrero – Workers World, 2023;

- Amílcar Lopes Cabral (1924-1973), Lucy Burnett, Black Past, 2009;

- CABRAL, Amílcar, António Ferraz de Oliveira, Global Social Theory;

- Amílcar Cabral, Wikipedia.