Manuel Figueira and the Cape Verdean Cultural Renaissance

Manuel Figueira In The Lisbon Years

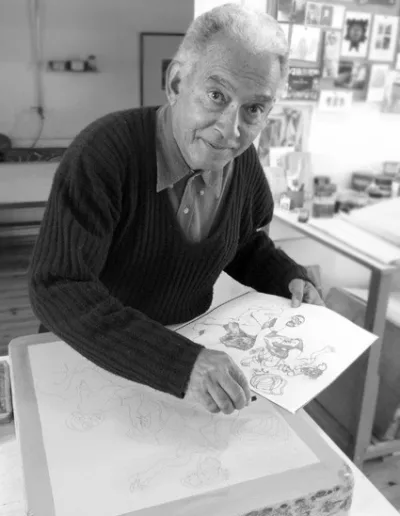

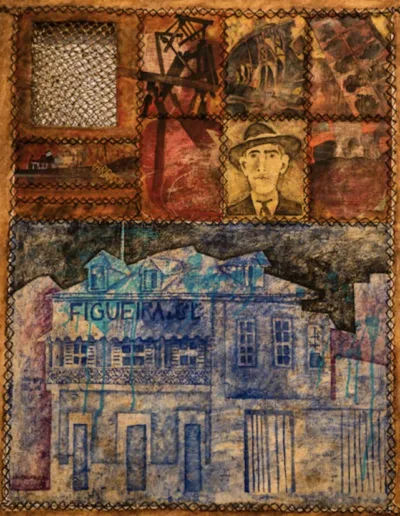

In 1960, something extraordinary happened. Manuel Figueira, age 22, left for Lisbon to study art. He became the first Cape Verdean ever admitted to the Escola Superior de Belas Artes de Lisboa. Think about that. Nearly 500 years of Portuguese rule, and he was the first.

Lisbon in the 1960s was a strange place to be African. Salazar’s Portugal clung to its colonies, while the rest of Europe relinquished theirs. The city was beautiful and suffocating, cultured and provincial. At the art school, Figueira studied the European masters while Portugal fought wars in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau to maintain its empire. He learned to paint like a European while his homeland struggled toward a freedom nobody reasonably believed would come.

But Lisbon gave him more than technique. He found the underground — artists like Gil Teixeira Lopes and Eduardo Nery who questioned everything the regime held sacred. He discovered movements such as Neorealism (with its focus on workers and peasants), Surrealism (which explored dreams and nightmares), and Pop Art (characterised by its commercial swagger). He absorbed it all. More importantly, he met Luísa Queirós, a Portuguese artist who would become his wife and collaborator. Together, they imagined a different future.

Figueira stayed in Lisbon for fourteen years. He could have stayed forever. He was establishing himself, showing in galleries, and teaching. Portugal was changing — the Carnation Revolution would come in 1974, and democracy would follow. A successful African artist in Lisbon was still rare enough to be valuable. He had made it.

Then, on July 5, 1975, Cape Verde became independent, and everything changed.

Coming Home to Build a Nation

The new government called its artists home. Come back, they said. Help us figure out what Cape Verde means. Figueira and Luísa packed their life into crates and sailed for Mindelo.

Try to understand what they were returning to. In 1975, Cape Verde had no museums, art schools, or galleries to speak of. The country had ten islands, nine of them inhabited, with a population scattered from Santo Antão in the north to Brava in the south. Half the Cape Verdeans in the world lived somewhere else — in Lisbon, Boston, Rotterdam, Dakar. The question wasn’t just what Cape Verdean art should look like; it was also what it should represent. The question was whether there was such a thing as Cape Verde at all.

Figueira’s answer came in 1976. Along with Luísa and another artist named Bela Duarte, he founded the Cooperativa da Resistência. The name mattered. Resistance. Not against the Portuguese — they were gone. Resistance against forgetting. Against the erosion of memory that threatens every small culture in a large world.

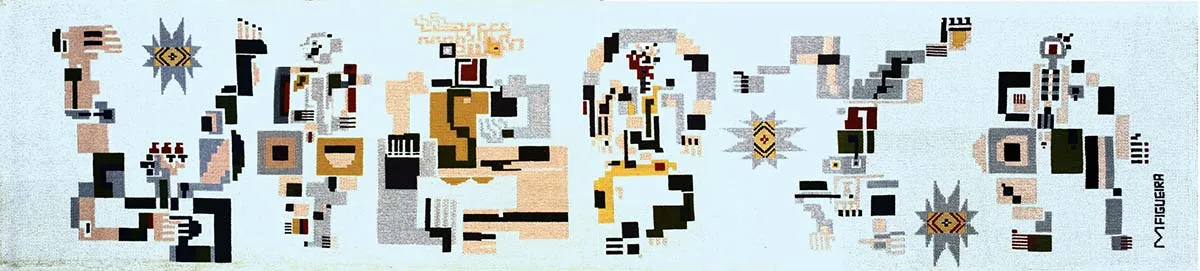

The Cooperative focused on panu di téra (or pano di terra), the traditional Cape Verdean cloth that had been woven in the islands since the 1500s. These cotton textiles, dyed indigo and white in intricate geometric patterns, had once served as a form of currency. Slave traders used them to buy human beings on the African coast. Now they were disappearing. The old weavers were dying. Their children had other dreams.

Figueira spent months in the mountains of Santo Antão and the valleys of Santiago, learning from masters like Nhô Damásio and Nhô Griga. These men knew patterns that existed nowhere else on earth — designs that merged African technique with Islamic geometry, Portuguese influence with something entirely Cape Verdean. Figueira sat there, at their looms, his painter’s hands learning the weaver’s rhythm, and he documented everything: patterns, techniques, the songs weavers sang to keep time.

The National Project

From 1978 to 1989, Manuel Figueira directed the Centro Nacional de Artesanato. The title sounds bureaucratic, but the work was revolutionary. He turned a few rooms in Mindelo into a laboratory where tradition met experiment. Young people came to learn weaving, but Figueira taught them more than technique. He taught them to see their culture as a living thing.

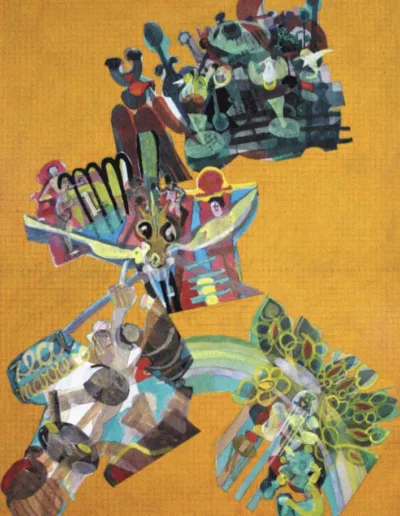

Under his direction, panu di téra evolved. Traditional patterns appeared on everyday-life objects such as lampshades and handbags. Ancient motifs inspired contemporary tapestries. The cloth that slaves had once bought became a symbol of freedom. Fashion designers in Lisbon and Paris began to take notice. What Figueira understood — what he made others understand — was that tradition didn’t mean repetition. It meant conversation. The past speaks to the present, arguing at times, and finding common ground.

Meanwhile, he painted. His studio on Avenida Marginal became Mindelo’s unofficial cultural centre. Young artists dropped by to argue and learn. Musicians came to play. Writers read their work. The space smelled of oil paint and coffee, cigarette smoke and the sea.

Manuel Figueira And The Art Itself

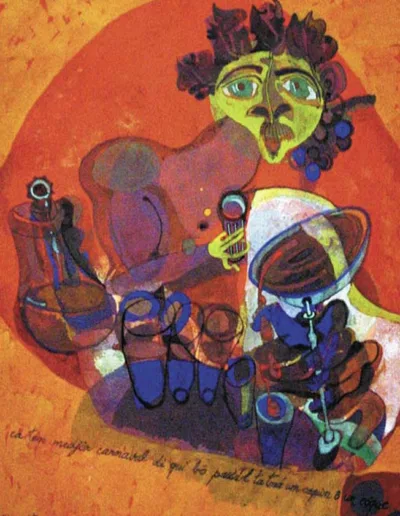

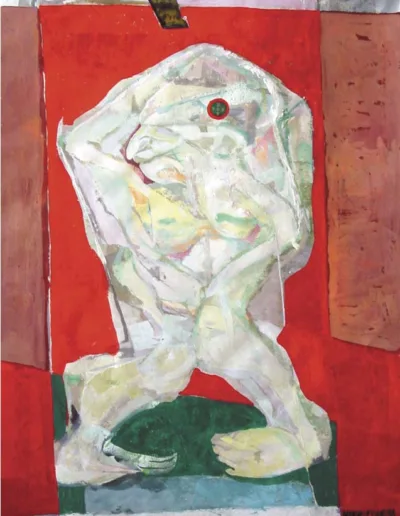

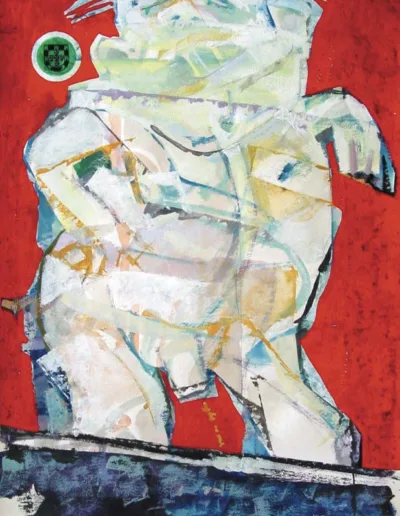

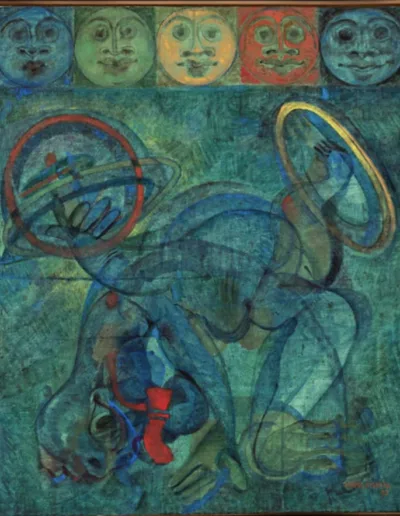

“I have been a figurative artist, but my reference on colour is an abstract one.”

Manuel Figueira once said. It’s the kind of statement that sounds simple until you think about it. He painted what he saw — fishermen, market women, children playing — but the colours came from somewhere else, not from observation but from emotion, memory, dream.

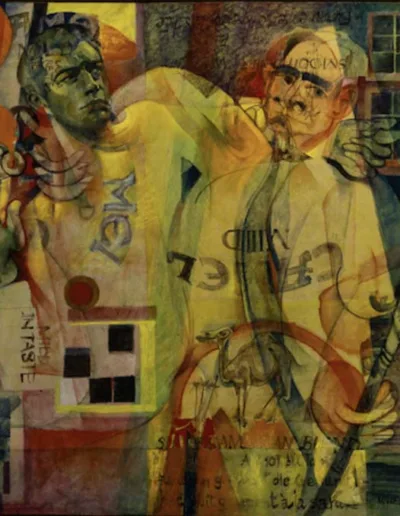

Look at his work from different periods, and you can read Cape Verde’s autobiography. The paintings from the 1960s are dark, cramped, and filled with a sense of anger. Colonial subjects painted in colonial colours. Then comes 1974, and suddenly the canvases explode. Reds like volcanic fire. Blues deeper than the channel between Brava and Fogo. Yellows like the drought-scorched hills of Maio. He painted Cape Verdean faces with European techniques and African colours. He made the familiar strange and the strange familiar.

His process was deliberate but not precious. He worked every day, treating art like fishing or farming — something you did regardless of inspiration. The paintings accumulated: portraits of independence leaders, abstractions based on weaving patterns, and landscapes that looked like music. He worked in oil, gouache, watercolour, whatever was at hand. During the difficult years following independence, when art supplies were scarce, he created his own pigments from volcanic earth and plants.

International galleries started noticing. A show in Vienna in 1963. Another in Rio de Janeiro. Washington, Seville, Brussels. Critics struggled to categorise him. Was he an African artist? A Portuguese artist? A post-colonial artist? Figueira ignored the labels and kept painting.

Manuel Figueira’s Recognition Without Compromise

The 2005 retrospective changed everything. Perve Gallery in Lisbon organised “Visões do Infinito” — 126 works spanning forty years. Portuguese critics, who had ignored Cape Verdean art for decades, suddenly discovered Figueira. Here was an artist who had synthesised European modernism with African aesthetics, creating something genuinely new. The Museum of Ovar acquired his work. So did the United Nations. Collectors who had never heard of Cape Verde started asking about the artist from Mindelo.

But success didn’t change his routine. Every morning, he climbed the stairs to his studio. Every afternoon, he could be found at the Cooperative, teaching young weavers or experimenting with dyes. He won prizes — the Jaime Figueiredo Award in 1988 and the Volcano Medal in 2000 — and displayed them without ceremony, more interested in the work ahead than in the work behind.

His brother Tchalé had also become an artist, though by a different route. While Manuel studied in Lisbon, Tchalé worked the Rotterdam docks, then discovered art in Basel. The brothers set up studios near each other in Mindelo, their different journeys converging in the same harbour. Where Manuel was methodical, Tchalé was explosive. Where Manuel preserved, Tchalé provoked. Together, they expanded the range and possibilities of Cape Verdean art.

The Long Teaching

Teaching obsessed Figueira more than fame. Not teaching in the formal sense — though he did that too — but rather the daily transmission of knowledge. He firmly believed that the culture survived through hands, not books. If a young woman came to learn weaving, he’d spend hours showing her how to read the patterns and how each design carried history. A painter would ask about colour, and Figueira would take him to the market, pointing out the exact shade of red in a vendor’s tomatoes, the specific blue of a fisherman’s boat.

He had no patience for what he called “airport art” — the simplified, sanitised crafts made for tourists. Real Cape Verdean art, he insisted, should challenge, surprise, disturb. It should prompt Cape Verdeans to see themselves differently and encourage foreigners to reevaluate their assumptions. He constantly fought against the reduction of Cape Verdean culture to morna music and picturesque beaches. The islands contained multitudes, he said. The art should show that.

The Cooperative evolved into the Centro Nacional de Arte, Artesanato e Design. The name change mattered to Figueira, not just in crafts, but also in art and design; not just preserving the past, but also creating the future. By the time he stepped down as director in 1989, hundreds of artists had passed through the centre. They spread across the islands and the diaspora, carrying techniques and, more importantly, attitudes. You could be from a small island and make universal art. You could honour your grandmothers and still be contemporary.

What Remains of Manuel Figueira

When Manuel Figueira died on October 8, 2023, Cape Verde’s president referred to him as “the father of our visual culture.” It wasn’t hyperbole. Before Figueira, Cape Verdean art was largely invisible, even to the Cape Verdeans themselves. After him, it was unavoidable.

Visit Mindelo today, and his influence is everywhere. The National Centre for Art, Craft, and Design is situated in a beautiful building near the port. Its galleries are filled with work that wouldn’t exist without Figueira’s foundation. Young artists paint murals inspired by his paintings, and Fashion designers in Praia create clothes using panu di téra patterns that he helped save from extinction. The traditional cloth itself, once produced by a handful of elderly weavers, is now taught in schools and exported worldwide.

But influence is more than technique. Figueira gave Cape Verdean artists permission to be themselves. To paint the drought and the emigration, the joy and the saudade. To use European techniques without apology and African subjects without explanation. To be small and essential, local and universal, traditional and radical all at once.

His paintings now hang in collections from New York to Beijing. The prices have become ridiculous—tens of thousands of euros for works he once traded for meals. But the real collection is harder to catalogue: the thousands of people who learned from him, argued with him, were changed by him. The weavers who still sing the songs he transcribed. The painters who mix colours the way he taught them. The children who grow up thinking it’s normal for a small African nation to produce world-class art.

The Deeper Pattern

There’s something else about Figueira, something more challenging to define. He understood that culture is how a people survive. Not just physically — anyone can eat and sleep and reproduce — but survive as themselves. Cape Verde could have disappeared after independence, its people scattered, its traditions dissolved into the larger currents of African or Portuguese culture. That it didn’t — that Cape Verde became more itself rather than less — owes much to artists like Figueira who insisted on the particular, the specific, the irreplaceable.

He knew that every pattern in panu di téra was a book, every colour a vocabulary. Lose the patterns and you lose the language. Lose the language and you lose the thoughts that can only be thought in that language. He fought against that loss with the devotion of someone who understood what was at stake.

The last time anyone saw him painting, three days before his death, he was working on a portrait of a young weaver at her loom. The painting remains unfinished. The woman’s hands are complete, captured in the act of pulling thread through warp, but her face is barely sketched. Some have suggested completing it, but Luísa, his widow, refuses. The incompleteness, she says, is honest. The work continues. The pattern extends beyond any single weaver, any single artist, any single life.

That may be Figueira’s truest legacy. Not the paintings in their climate-controlled galleries or the prizes in their velvet boxes, but the understanding that culture is work — daily, demanding, essential work. That a nation is made not just of constitutions and currencies but of colours and patterns, stories and songs. That resistance means remembering. That independence means creating.

Manuel Figueira passed away, but the work he started remains very much alive. In Mindelo, Praia, the mountains of Santo Antão, and on the beaches of Sal, people are weaving, painting, and creating. They are having the conversation he started — between past and future, between here and elsewhere, between what was nearly lost and what might yet be found. The port of Mindelo never sleeps. Neither does the culture Manuel Figueira helped create. It works through the night, threading tomorrow through today, pattern by pattern, colour by colour, resistant and free.

Bibliography

- Manuel Figueira, Cape Verde, Centro Portugues de Serigrafia (CPS);

- Manuel Figueira: The revival of popular culture, PIASA Auction House, 2020;

- Manuel Figueira, Arts and Literature, Minnie Freudenthal, De Outra Maneira 2024;

- Manuel Figueira, Cabo Verde – Biografia (PDF), Perve Galeria;

- Manuel Figueira (1938 – 2023), Perve Galeria;

- Cabo Verde – Faleceu Manuel Figueira, artista múltiplo (in Portuguese), The Vatican News;

- Masters we need to master: The Cape Verdian brothers, Manuel and Tchalé Figueira, Valerie Kabov, Art Africa;

- Manuel Figueira on Wikipedia.