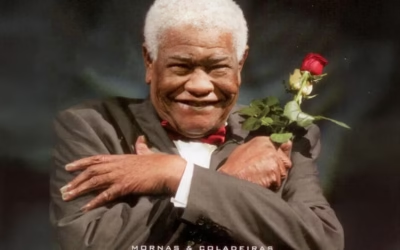

Orlando Pantera: Great Musical Genius Who Died Too Soon

The story of Orlando Pantera serves as a tribute to an artist who never achieved stardom but remains a powerful symbol of Cape Verdean identity and culture. In 33 years, he supported and influenced many famous artists and, most importantly, changed how the country heard itself. That may be legacy enough.

A Week Before Fame

Orlando Monteiro Barreto was seven days away from recording his first album when he died. The 33-year-old Cape Verdean musician, known as Orlando Pantera, had booked studio time in Paris for March 8, 2001. The album, “Lapidu na Bô,” would have introduced his voice to the world. Instead, acute pancreatitis killed him on March 1 in Praia, the capital of his island nation.

Twenty-four years later, that unrecorded album haunts Cape Verdean music. Pantera’s compositions live on through other singers, his innovations echo in a generation of internationally successful artists, and his name appears on government awards. Orlando Pantera became more influential, even after his death, than many musicians achieve in their whole careers.

Orlando Pantera Transforms Women’s Music

Pantera’s breakthrough came through batuku, a traditional music form created and dominated by women, who, sitting in circles, beat makeshift drums and improvised verses. Colonial authorities had banned these gatherings, considering them too African, too unruly. After independence in 1975, young Cape Verdean musicians began exploring their suppressed heritage. Pantera went further than most.

In the early 2000s, urban musicians reworked batuku, taking its rhythmic patterns and transposing them to guitar. Pantera was a significant force in bringing batuku tones and rhythms to the guitar and acoustic music. As a person in Catarina Alves Costa’s documentary says, “he puts batuku on the family table.”

He would travel to tabancas (villages), attending fiestas and traditional batuku ceremonies, collecting these traditions and bringing them into contemporary musical contexts. His song “Batuku está na moda” declared through its lyrics that ‘now it’s the time for batuku,’ while the rhythm itself was batuku.

Early Recognition

Born on November 1, 1967, in São Lourenço dos Órgãos on Santiago Island, Pantera joined several musical groups in the early 1990s, including Pentágono, the Cape Verdean Jazz Band quintet, and Arkor. His compositions earned him a nomination for Composer of the Year in 1993.

Three of his songs appeared on “Porton d’nôs Ilha” (Gates of the Island), a 1994 album by Os Tubarões that mixed morna, coladeira, funana, and tabanca. He also collaborated with the Portuguese theatre company Clara Andermatt, contributing to productions such as “Dan Dau” and “Uma História da Dúvida.”

In 2000, Orlando Pantera won the Revelation Award at the Sete Sóis Sete Luas Festival on Santo Antão island. Recognition was building. International opportunities beckoned.

Beyond Music

Pantera worked with street children in Assomada, a small city near Praia. He was deeply engaged in building a society still defining itself after independence. His lyrics told stories about people living in Santiago’s interior and rural areas, often using archaic Creole words to capture the essence of contemporary life in the region.

There was a strong sense of humour in his music, according to filmmaker Costa, who spent time documenting Cape Verde’s art scene in 2000. His approach to traditional music differed from typical masculine perspectives. When he sang about women and relationships, he tried to bring the strong character of Cape Verdean women into his music.

The Generation That Followed Orlando Pantera

Music critics call them the “Pantera Generation”: Lura, Mayra Andrade, Tcheka, Princezito, and Sara Tavares. Several studied under Pantera directly. Their sound combines elements from every Cape Verdean music style with influences from the African mainland and global diaspora.

Lura recorded five of his compositions on her album “Di Korpu Ku Alma.” “I thought that this was my music when I heard him,” she said. Mayra Andrade covered four of his songs on “Navega.” Both artists, along with Tcheka, are described as searching for their own music while staying rooted in Cape Verde’s stylistic diversity.

Songs like “Tunuka,” “Lapidu na bô,” “Na Ri Na,” “Dispidida,” “Vasulina,” and “Regasu (Seiva)” became his best-known compositions, later performed by artists including Voginha and Leonel Almeida. The annual “Orlando Pantera Awards,” held by Cape Verde’s Ministry of Culture, bear his name.

Cultural Influence of Orlando’s Work

In Europe, Cape Verdean music is primarily associated with morna, mainly due to Cesária Évora‘s international success. But funana and batuku had been looked down upon by colonial authorities. Pantera became part of a post-independence movement to reclaim suppressed musical traditions.

Batuku was repressed during the colonial period by the Catholic Church due to the sensuality of its dance and by Portuguese administrative authorities because of the alleged disorder of these festive moments. Pantera helped bring batuku to the elites. The tradition of women gathering to play, tell stories and dance wasn’t taken seriously by Cape Verde’s upper classes.

Orlando’s influence continues with younger artists like Dino Santiago, who works with Santiago Island rhythms, and rap artists who incorporate traditional roots into contemporary beats.

Preserving the Memory of Orlando Pantera

Pantera’s daughter, Darlene, was six when he died. Now in her thirties, she has spent years researching her father’s life and work. Her efforts led to a documentary by filmmaker Catarina Alves Costa, featuring contemporary interpretations by artists like Mayra Andrade and Princezito.

The Fundação Orlando Pantera works to preserve his legacy, supporting theatrical tributes and educational programs. Recent projects include fruitful collaborations between Portuguese and Cape Verdean cultural institutions to ensure that his innovations reach new audiences.

Unfinished Business

The timing of Pantera’s death amplifies its tragedy. He died without recording any albums of his own, always working behind the scenes but finally ready to take centre stage. Two days after his death, he was supposed to leave for Paris to record “Lapidu Na Bo,” an album awaited as his breakthrough.

Although Pantera died without leaving any recorded music, his innovations continue to shape Cape Verdean music. The artists he influenced have achieved the international recognition that eluded him, carrying his musical vision to global stages.

Bibliography

- Orlando Pantera (movie) – Catarina Alves Costa, 2025, IndieMusic;

- Orlando Pantera and Music of Cape Verde, Wikipedia;

- Orlando Monteiro Barreto (Orlando Pantera), Personalities, Cabo Verde Info;

- Pantera, ACCA Production, Companhia Clara Andermatt.