Phoenix Atlantica: The Unique Capeverdean Date Palm

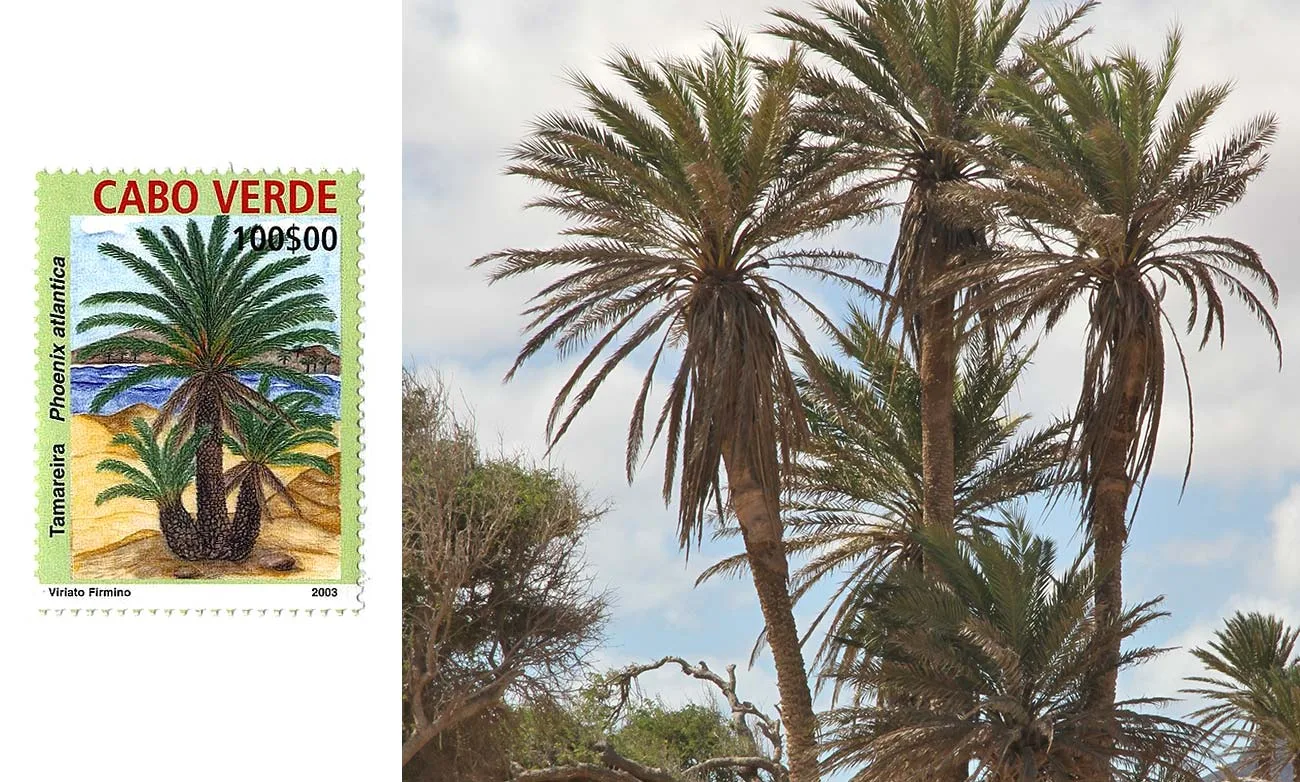

Clusters of emerald-green palms rise rebelliously from the dry and salty land of Sal. These are Phoenix atlantica, the endemic Cape Verdean date palms, known locally as “tamareira.”

They are known for their survival in an environment where little else can, enduring extreme environmental challenges such as constant droughts and salty trade winds. Long cherished by Cape Verdeans as their own distinctive palm, Phoenix atlantica stands as an icon of local natural heritage. It’s a tree that grows wild nowhere else in the entire world. Yet for all its resilience, this palm’s very existence is under threat, and its true origin has been a botanical mystery for decades.

The Discovery and Taxonomic Puzzle

The Cape Verdean date palm first came to scientific attention in the 1930s, when French botanist Auguste Chevalier encountered unusual palm groves on the islands of Sal and Santiago. Chevalier formally described it as Phoenix atlantica in 1935, noting how these palms didn’t neatly match any known species.

They grew in clumping thickets of approx. 2 to 6 trunks, up to 15 meters tall – unlike the single-trunk Canary Island date palm – yet they also differed from the typical cultivated date palm of North Africa. Chevalier observed traits of both the wild Phoenix canariensis and the domesticated Phoenix dactylifera in them.

This hybrid of characteristics puzzled taxonomists: was P. atlantica a distinct wild species, a naturally occurring hybrid, or simply a feral offshoot of cultivated date palms? For decades, it remained an “imperfectly known” taxon with an unresolved status.

Scientists who later studied the palm carried this debate forward. A comprehensive monograph published in 1998 still listed P. atlantica as enigmatic, and early DNA analyses in the 2000s confirmed that it was genetically isolated from other date palms. This supported the idea that Cape Verde’s tamareira was not just an escaped farm palm, but something unique.

Indeed, by 2006, researchers had demonstrated that P. atlantica is clearly distinct from its mainland relatives, being likely closest to P. dactylifera but with its own unique genetic identity.

Still, the question lingered: How did date palms get to these remote islands? Were they ancient natives or the feral progeny of dates brought by human hands? The story was about to get even more interesting.

Biology and Description of Phoenix atlantica

Cape Verde’s date palm exhibits a hardy, clustering growth form that is well-adapted to harsh conditions. A mature tamareira typically has a crown of arching, pinnate leaves 2–3 meters long atop multiple slender trunks. Unlike the stout solitary trunk of the Canary Island palm, P. atlantica often sprouts new stems at its base, forming family-like clumps. Older clumps can tower 10–15 m high, their grey-brown trunks about 30–45 cm in diameter.

Male and female flowers grow on separate trees (as is characteristic of date palms), and when pollinated, the female palms produce oval drupes about 2 cm long. These fruits start yellowish and may blush orange-red when ripe. They are technically edible – local children sometimes sample the sweet flesh – but the pulp is scant and not a significant food crop. In appearance, P. atlantica looks much like a scrappy wild cousin of the domesticated date palm: its fronds are slightly shorter and stiffer, and its clusters of slim trunks immediately set it apart from any plantation-grown palm.

Cape Verdean date palms often grow in multi-stemmed clusters, reaching heights of up to 15 m, an adaptation that helps them survive harsh arid conditions. Each palm bears feathery fronds and (on female trees) hangs stalks of small dates that ripen to yellow or pinkish hues. The dense foliage provides precious shade in the desert landscape.

Despite their rugged look, these palms are relatively slow-growing and long-lived. Their deep root systems seek out underground moisture, enabling them to survive through multi-year droughts. Botanists note that Phoenix atlantica can be easily distinguished from the ornamental Canary Island palm by its slender clustering habit and from the classic Arabian date palm by subtle flower differences (such as pointed petals on male flowers). The Cape Verde palm’s ability to sucker (produce offshoot trunks) is actually more akin to the wild African date palm (Phoenix reclinata), hinting at evolutionary adaptations for resilience. Overall, tamareira is a textbook example of island adaptation – tough, unassuming, yet vitally suited to its niche.

Habitat and Ecology

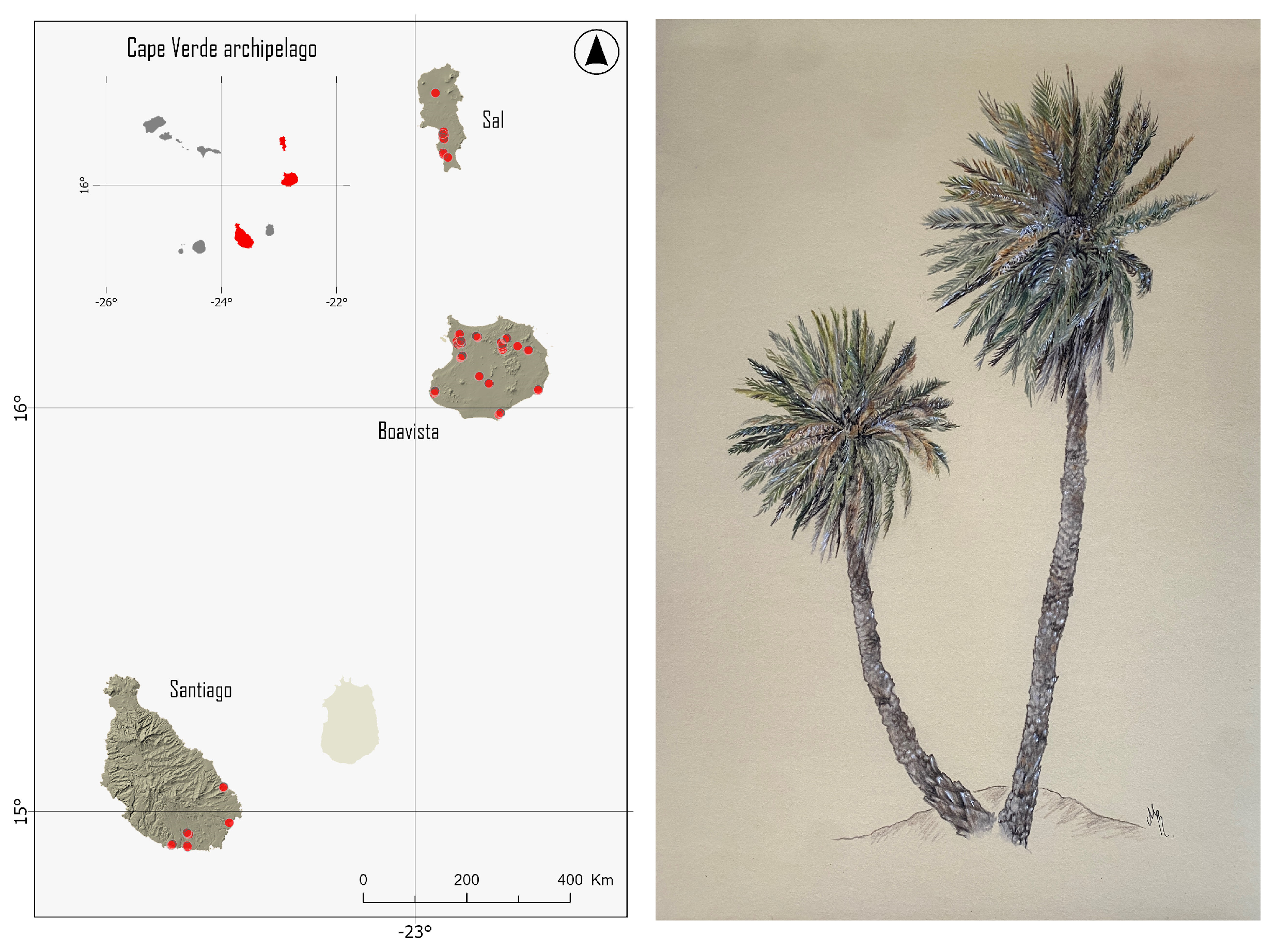

Phoenix atlantica has a fragmented distribution across Cape Verde, confined to pockets of habitat where water appears – however briefly – in the desert. It grows primarily in the drier, lowland islands and coastal areas. Historically, natural populations were recorded on the eastern islands of Sal, Boa Vista, and Maio, as well as in parts of Santiago, and possibly on the uninhabited islet of Santa Luzia. These islands have flat or gently rolling terrain and an arid climate, receiving as little as 100–300 mm of rain per year in sporadic downpours.

The palms typically anchor themselves in seasonal streambeds (ribeiras) and at the foot of rocky slopes, where occasional rainwater funnels and soaks into the ground. In such spots – a cleft in a canyon wall, the edge of a salt flat, or a low-lying oasis – tamareiras find just enough moisture to persist. They have been observed from near sea level up to about 800–1000 m elevation in sheltered valleys, though most occur in coastal plains and dry gulches.

Ecologically, these palms act as oasis creators. Their presence often signals a groundwater vein or intermittent spring. The shade from their fronds cools the soil. It conserves humidity, allowing other native plants to grow beneath – something invaluable on islands that count only a half-dozen native tree species in total. Under a stand of Phoenix atlantica, one might find grasses, succulents, or seedlings that wouldn’t survive in open sun. In this way, the Cape Verde date palm serves as a keystone species for microhabitats.

It is also one of the very few indigenous trees adapted to Cape Verde’s extreme dryness (global conservation groups note it as one of just five truly native trees in the country). By stabilising soils and offering refuge for wildlife, these palms play an outsized role in their environment.

Many Phoenix atlantica groves are located near old wells, villages, or watering sites – raising the classic “chicken or egg” question. Did early settlers plant palms where they settled, or did they settle where palms already grew?

Historical records and photos suggest a bit of both. In some cases, villages like Palmeira (literally “palm tree” in Portuguese) on Sal Island likely took their name from existing palm groves, indicating P. atlantica was a natural feature that humans gravitated toward. In other cases, people may have deliberately planted date seeds at oasis sites for future harvests or shade.

Over centuries, the palms and people formed a tight-knit association on these islands. Even today, a traveller crossing the bleak desert interior of Sal or Boa Vista will often spot a distant clump of green palms marking the location of a hidden spring or abandoned hamlet – a living signpost of water in an unforgiving land.

Picture: Map showing sample locations of palms collected from three islands in Cape Verde: Sal, Boavista, and Santiago (left). Drawing of P. atlantica by Guacimara Arbelo Ramírez (right), © A Comparative Genetic Analysis of Phoenix atlantica in Cape Verde, DOI:10.3390/plants13162209

Cultural Significance and Uses

Cape Verde’s tamareira is woven into the fabric of island life, particularly on Sal Island, where it provides rare greenery in a salt-flat desert. Locals long valued these palms for convenient reasons:

1. Shade and Shelter

A stand of date palms offers relief from the intense tropical sun. In villages and pastures, people and livestock alike rested under the palms’ fan of fronds. Even a small oasis of tamareiras can feel like an oasis for the soul, a patch of cool in the heat.

2. Materials

The palm’s wood and leaves have traditionally been used in construction. Sturdy midribs of fallen fronds serve as roof thatch supports or fencing, while dried leaflets are woven into mats, baskets, and brooms. The trunks, though narrow, can be used as poles in rustic buildings. In a land with few large trees, every part of the palm found a use as a building material or craft supply.

3. Food and Fodder

Although not a commercial crop, the dates of P. atlantica are occasionally eaten. Children snack on the sweet little fruits despite the thin flesh, and in lean times, people have fermented the sugary sap to make a palm wine or fed the fruits to animals. The yellow-orange dates, about the size of olives, were once sold locally in markets. However, they were never exported, and the palm was not actively farmed for fruit.

4. Symbolic Importance

Beyond these utilitarian aspects, the Cape Verde date palm holds symbolic importance. It is a hardy survivor, much like the Cabo Verdean people who have thrived on these harsh islands. In local Creole oral history and song, references to “tamareira” evoke home and endurance. Modern islanders take pride in this endemic palm – it’s a living emblem of their unique flora.

In recent years, as eco-tourism grows, Phoenix atlantica has also become a point of interest for visitors. Guides on Sal Island will point out the wild palm groves at places like Fontona oasis or the dry creek north of Murdeira, explaining how these greenery patches are relics of the original island ecosystem. To stand under a tamareira clutch on Sal, listening to the wind rattle its fronds, is to connect with centuries of island history and nature.

An Ancestry Mystery: Wild or Feral?

For much of the 20th century, botanists debated whether Phoenix atlantica was truly a wild species that had evolved in isolation or, rather, a population of escaped cultivated date palms. Cape Verde was uninhabited by humans until the 15th century, so if the palms arrived with people, they’ve only been free for about 500 years – a blink in evolutionary time. Yet if they predated humans, how did such large, heavy seeds reach these oceanic islands? This conundrum made P. atlantica a fascinating case study in plant biogeography.

Recent scientific sleuthing has shed dramatic new light on the palms’ origin. Between 2023 and 2025, a team of researchers conducted a genomic and morphometric analysis of Phoenix atlantica. The research was thorough. They even extracted DNA from a palm specimen collected by Chevalier almost a century ago, in 1934. The results, published in 2025, delivered a surprise. Cape Verde’s date palms appear to descend from the Middle Eastern date palm, Phoenix dactylifera. In other words, the island palms are likely the feral offspring of domesticated date trees that went wild centuries ago. The analysis showed that P. atlantica’s DNA is nested within the family tree of cultivated date palms, not separate from it. Its seed shapes even bear the hallmarks of ancient domestication (more elongated than truly wild dates), implying a cultivated origin.

How might this have happened? One scenario is quite prosaic. As lead researcher, Jerónimo Cid Vian speculates, “one or a few date seeds escaped from their grove” long ago. Perhaps Portuguese settlers in the 16th century planted date palms at a watering hole on Sal or Boa Vista; birds or goats could have scattered seeds beyond the tended groves. Those strays took root in the wild and, over generations, adapted to Cape Verde’s harsher climate. With no irrigation or cultivation, natural selection would favour the hardiest individuals. Over hundreds of years, these runaway date palms evolved distinct traits, essentially re-wilding themselves into a unique population.

The notion that Cape Verde’s beloved “native” palm might actually be an introduced species gone wild is provocative. In biological terms, it blurs the line between what we call a species versus a variety or landrace. If Phoenix atlantica can still interbreed with other date palms and share most of their DNA, should it remain a separate species? The question is scientifically messy, and even the experts find it fascinating. Some argue that since the Cape Verde palms have unique genetic combinations and survive independently, they have earned species status as an “incipient species” in the making. Others note that classifying it as just a type of Phoenix dactylifera could aid agricultural research by highlighting its close kinship.

Researchers like Cid Vian emphasise that taxonomic debates should not undermine the palm’s cultural and ecological significance to Cape Verdeans, who have referred to it as tamareira for generations and view it as part of their natural heritage, regardless of its ultimate origin. As one scientist mused, if humans were responsible for creating this wild palm population, it only adds to the story of humans and nature coexisting in the archipelago.

Conservation Status and Outlook

Regardless of its origins, Phoenix atlantica faces very real threats today. It is officially classified as an Endangered species on the IUCN Red List, with field surveys suggesting only a few hundred mature palms remain in the wild. Its distribution is severely fragmented – tiny groves scattered across islands – and many populations are in decline. In some areas, ageing palms have not been replaced by young ones, hinting at poor regeneration.

The challenges are numerous: prolonged droughts and shifting climate patterns have made natural water even scarcer; wandering goats and other livestock nibble on tender seedlings in the dry season; and human development has disturbed some of the precious oasis habitats. On Sal Island, for instance, expanding tourism infrastructure requires careful planning to avoid depleting the water table that sustains the last remaining palm groves.

Another concern is the introduction of foreign palms. Ornamental Phoenix canariensis (Canary Island palms) and even imported P. dactylifera are now planted in towns for landscaping purposes. These could potentially hybridise with the native tamareiras or out-compete them if they escape into the wild. Conservationists thus urge the protection of the genetic integrity of P. atlantica – keeping its populations isolated from introduced relatives wherever possible.

The good news is that awareness of this unique palm has grown in recent years. Local universities and international botanists have begun conservation programs to propagate and safeguard the species. Small nurseries in Cape Verde (for example, an ecopark on Sal) are now cultivating seedlings collected from wild palms. These efforts aim to create backup populations and provide stock for replanting degraded sites. Scientists have even recommended establishing seed banks from the robust wild groves on Boavista and Sal, as a hedge against extinction.

Protecting Phoenix atlantica is not just about saving a plant – it’s about preserving a piece of Cape Verde’s identity and natural history. The palm may hold genetic secrets for crop resilience (its genes could help farmed date palms adapt to heat and drought), making it globally important as climate change stresses agriculture.

Locally, the palms are an integral part of the landscape that sustains rural life and could serve as a focal point for eco-tourism. In recognition of this, discussions are underway to strengthen legal protection for remaining wild groves and possibly designate specific palm oasis sites as protected natural monuments. Community engagement is key: Cape Verdeans are being encouraged to take pride in their tamareira and participate in its conservation – from planting young palms to controlling goat browsing.

Thoughts on Cape Verdean Date Palm

This unique tree bridges the human and natural worlds of Cape Verde: planted (possibly by settlers), it was then reclaimed by nature, and now requires human help once more to ensure its future. The coming years will determine whether the lonely date palms of Sal Island’s desert will continue to greet travellers for generations to come. With robust conservation action and respect for traditional knowledge, Phoenix atlantica can endure – an indomitable green testament to Cape Verde’s blend of history, biology, and hope.

Bibliography & Further Reading

- Phoenix atlantica, IUCN Red List of Threatened Species;

- Phoenix in the Cape Verde Islands, Henderson, S., Gomes, I., Gomes, S., & Baker, W. Palms 47(1), 2003;

- A Comparative Genetic Analysis of Phoenix atlantica in Cape Verde, Sonia Sarmiento Cabello, Priscila Rodríguez Rodríguez, Guacimara Arbelo Ramírez, Agustin Naranjo-Cigala, via ResearchGate;

- A nearly century-old dead date palm tree helped solve an ancestry mystery. The iconic Cape Verde date palm comes from cultivated trees gone feral, Susan Milius, ScienceNews, 2025;

- A Comparative Genetic Analysis of Phoenix atlantica in Cape Verde, Sonia Sarmiento Cabello, Priscila Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Guacimara Arbelo Ramírez, Agustín Naranjo-Cigala, Leticia Curbelo, Maria de Monte da Graca Gomes, Juliana Brito, Frédérique Aberlenc, Salwa Zehdi-Azouzi and Pedro A. Sosa, Plants 2024, 13(16), 2209;

- Phoenix atlantica: A comprehensive Growing Guide for Enthusiasts & Collectors, Viriar, 2025;

- Phoenix atlantica, Palmpedia.

- Phoenix atlantica, Wikipedia.