Rissóis: Simple Recipe for These Tasty Pastries (Video)

Rissóis – Cape Verde’s Crispy, Creamy Hand Pies

In the warm kitchens of Cape Verde, where the scent of garlic and frying oil drifts through tiled courtyards and tin-roofed bakeries, one irresistible snack draws people together like few others: rissóis. These crescent-shaped, breaded pastries — golden and crisp on the outside, soft and creamy on the inside — are one of the most beloved finger foods across the islands.

Although their roots are distinctly Portuguese, rissóis in Cape Verde have developed a character of their own. Filled with local tuna or shrimp and adapted to homegrown tastes, they’re no longer simply “pastéis” — they’re part of the Cape Verdean culinary fabric. You’ll find them at family celebrations, in packed lunchboxes, on bakery trays beside fresh pão quente, or passed around at community gatherings, steaming hot and impossible to resist.

Step-by-Step: How Rissóis Are Made

Crafting rissóis is an act of patience and precision. Though not difficult, the process involves multiple steps, and it’s the kind of dish best prepared in batches — some to serve, some to freeze, and all to be enjoyed slowly.

1. Prepare the Filling

Start by sautéing finely chopped onion and garlic in oil until fragrant. Add shredded canned tuna (or chopped cooked shrimp), season with salt, pepper, and paprika. Slowly stir in a slurry of flour and milk, whisking over gentle heat until the mixture thickens to a creamy consistency. Set aside to cool.

2. Make the Dough

In a pot, bring water, a touch of oil or butter, and salt to a boil. Stir in all-purpose flour all at once, reducing the heat. Mix vigorously with a wooden spoon until the dough pulls away from the sides and forms a ball. Turn out and knead until smooth.

3. Shape the Rissóis

Roll the dough on a floured surface. Use a glass or cutter to create rounds. Place a spoonful of filling in the centre of each circle, fold over into a half-moon, and press edges firmly. Some cooks use the tines of a fork or a pastry cutter for a sealed edge.

4. Bread and Fry

Dip each rissol in beaten egg, then in fine breadcrumbs. Fry in small batches in hot oil (160–170°C) until evenly golden. Drain on kitchen paper. Serve warm or at room temperature.

This process can take a couple of hours, but for many Cape Verdean families, making rissóis is a group activity — shared between aunts, cousins, and children eager to pinch dough or sneak a bite.

Serving Suggestions and Storage Tips

- Best served warm, straight from the oil.

- Perfect as party food, arranged on platters with napkins or toothpicks.

- Can be frozen — both before and after frying. Just ensure a second fry is done gently, so the filling warms through without drying.

- Pairs well with: a crisp green salad, a squeeze of lemon, or a glass of ponche for a festive Cape Verdean snack moment.

Rissóis can even be served for lunch with rice and salad in some local cafés. But at their core, they remain a hand-held joy — meant to be shared, not plated.

A Story That Travels from Portugal to Praia

The origins of rissóis lie in Portugal, where they were once delicate pastries filled with minced meat or shrimp béchamel, served as a café treat. Introduced during colonial times, the concept migrated to Cape Verde and was transformed — first by necessity, later by creativity.

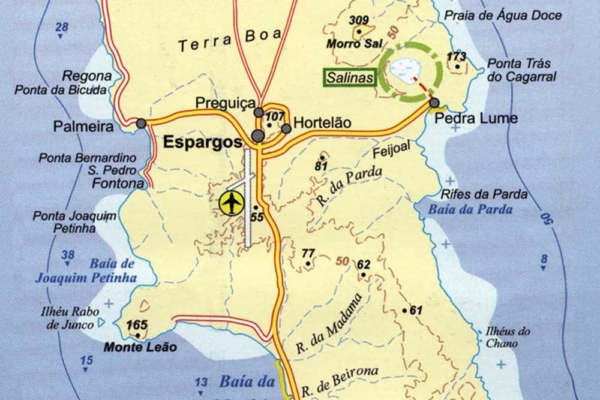

Tuna, abundant in Cape Verdean waters, quickly replaced imported meats as the standard filling for sandwiches. The dough evolved to match local preferences: it was slightly firmer, easier to fry without breaking, and was made without eggs or dairy in the dough itself. Cape Verdean rissóis, especially on São Vicente, Sal (e.g., in towns such as Santa Maria and Palmeira), and the Santiago islands, became deeper in flavour, sturdier in construction, and more generous in size.

Over time, these fried half-moons became a staple of island hospitality — served at birthdays, communions, beach picnics, street stalls, and even formal events. Few snacks in Cape Verde are as universally loved, or as versatile.

What Defines a Cape Verdean Rissóis?

The essence of a rissol lies in its contrasts: the crisp shell and the creamy core, the mild dough and the savoury filling. Cape Verdean rissóis differ from their European ancestors in several subtle ways.

- The Dough: Made with flour, water, oil, butter, and salt — boiled and stirred until it forms a smooth, elastic ball. Once kneaded and rested, it’s rolled thin and cut into rounds.

- The Filling: Most commonly tuna or shrimp, sautéed with onion, garlic, and herbs. The mix is then bound with milk and flour into a thick, creamy base that holds its shape when fried.

- The Crumb: After shaping, each rissol is dipped in beaten egg, rolled in breadcrumbs, and fried until golden-brown. The result is a delicate crunch that gives way to a soft interior.

Some cooks like to season the dough with a touch of pepper or nutmeg. Others add parsley or green pepper to the filling. The beauty of rissóis is that they allow minor variations — each family has its favourite.

Popular Rissóis Variants Across the Islands

Though tuna is the most popular filling — flavoured simply with garlic, onions, and sometimes tomato paste — other fillings reflect the diversity of island cuisine:

- Shrimp (Rissóis de Camarão) – Creamy, with a gentle sweetness and luxurious mouthfeel. Often served at weddings and formal receptions.

- Cheese or Requeijão – A vegetarian variant found in some modern cafés or for fasting periods.

- Minced meat (Carne) – Less common in Cape Verde, but appearing in urban bakeries and fusion menus.

Some cooks also experiment with chilli heat, lemon zest, or fresh herbs. Creativity is bound only by what’s available and what memories people bring to the kitchen.

More Than Just a Snack

In Cape Verde, rissóis are not just food — they’re social currency. When visiting a friend, you might bring a few wrapped in paper. When hosting a gathering, a plate of rissóis is expected, even if just as a nibble before the main course. For diaspora Cape Verdeans, making rissóis abroad becomes a nostalgic ritual, a way to recreate home with flour, fish and oil.

They also serve as an important bridge between generations. Children learn to shape rissóis from their mothers or grandmothers. Teenagers master the frying technique. Adults pass down variations and tricks. It’s culinary knowledge passed by hand, not written in cookbooks.

Bibliography / Sourdes

- Field observations and interviews with Cape Verdean home cooks (Sal and São Vicente, 2023–2024).

- Cape Verdean tuna rissois (rissois de atum) on Crumb Snatched blog;

- Rissois with shrimp filling (rissois de camarão) on Crumb Snatched blog;

- How to make Rissois de Camarão, Cabo Verde, 1-min Recipe Video by Prof Mele on Youtube;