Tchalé Figueira: Great Wanderer Who Painted His Way Home

Carlos Alberto Figueira never uses his birth name. In Mindelo, in Basel, in the galleries of Paris and New York, he’s Tchalé. Just Tchalé. The nickname stuck sometime in childhood, and like everything else about him, it refuses explanation. Ask him why Tchalé and he’ll paint you a picture instead — literally. Probably with a fat man in it, maybe a prostitute, definitely someone laughing at authority. The painting will tell you everything and nothing, which is precisely how Tchalé likes it.

Born in 1953, fifteen years after his brother Manuel (also a well-known artist), Tchalé grew up in the same streets of Mindelo, but saw a very different city. Where Manuel saw forms to study, Tchalé saw a circus. Where Manuel planned his escape to art school, Tchalé planned his escape, period. At seventeen, in 1970, he left Cape Verde for what he calls “national political reasons” — a phrase that encompasses a wide range of motivations when you’re young, Black, and living in the last European colony in Africa.

The official story goes: he went to Rotterdam. However, the real story suggests that Rotterdam was simply where the boat stopped first.

The Docks and the Discovery

Picture this: a kid from Mindelo, where the tallest building is three stories high, suddenly standing in Rotterdam’s sprawling industrial landscape. The port stretched forever — Ships from everywhere, going everywhere. Tchalé took a job on the docks because what else do you do when you’re seventeen, illegal, and strong? He loaded cargo from places he’d only seen on maps — if he’d seen them at all. Indonesian spices. German machinery. American cigarettes. Each crate was a possibility. Each ship is an escape route.

But Rotterdam was cold in ways that had nothing to do with the weather. The Dutch looked through him, not at him. The other dockworkers — Turks, Moroccans, Surinamese — had their own problems. Everyone was saving money to go somewhere else or bring someone here. Nobody was home. Nobody was making art. The work was hard and dull, and it paid just enough to keep you coming back, which is the worst kind of work there is.

So Tchalé started walking. And so he walked through Amsterdam, where the hippies thought Africa was a state of mind, and through Brussels, where the Congolese told him stories that made Cape Verdean problems seem no biggie. And he went through Paris, where the Senegalese intellectuals argued about Négritude in cafés he couldn’t afford. He spent months drifting, working when necessary, and moving when not. He went east into Germany, south into Italy. Some say he made it to Asia, though Tchalé never confirms or denies. The years between 1970 and 1974 remain deliberately vague, a blur of trains, borders, and odd jobs. “I was collecting myself. Piece by piece.” He says now.

Basel: The Accident of Art

He ended up in Basel by accident — or so he claims. The train was heading there, and he had just enough money for the ticket. Besides, he’d heard that they spoke German differently in Switzerland, which seemed interesting. He was twenty-one, had been gone from Cape Verde for four years, and still didn’t know what he was looking for. Then he saw someone painting in a park.

Not painting pictures and painting huge, wild, angry things. The artist turned out to be a student at the Kunstgewerbeschule Basel, and when Tchalé stopped to watch, the student asked if he wanted to try. Tchalé had never held a real brush. In Mindelo, art was something his brother Manuel did — serious, studied, proper. But here in Basel, with nobody watching, with no one knowing who he was or wasn’t supposed to be, Tchalé picked up the brush.

What happened next, funnily, depends on who tells the story. Tchalé says he painted:

“a disaster, but an interesting disaster.”

Others say he showed immediate talent. What’s certain is that he kept returning to that park, and eventually, someone suggested that he apply to the school. The idea seemed absurd. Him? In art school? With Swiss kids who’d been drawing since they could hold pencils? But Basel in 1974 was different from Basel today. The city was experimenting with international students, employing radical teaching methods, and exploring the idea that art could emerge from anywhere.

They let him in. Probably, he suspects now, to fill some kind of quota. He didn’t care. He had a student visa and a small stipend, and suddenly, amazingly, he had time to figure out what he wanted to paint.

The Swiss Years: Learning to Laugh in Paint

The Kunstgewerbeschule Basel from 1974 to 1985 was Tchalé’s real education, though not in the way the school intended. His professors wanted him to paint “African themes” — whatever that meant. They showed him books about “tribal art,” suggested he explore his “authentic voice.” Tchalé painted Swiss bankers with tribal masks. He painted African dictators in Alpine settings. He painted everything wrong, on purpose, until they stopped telling him what to paint.

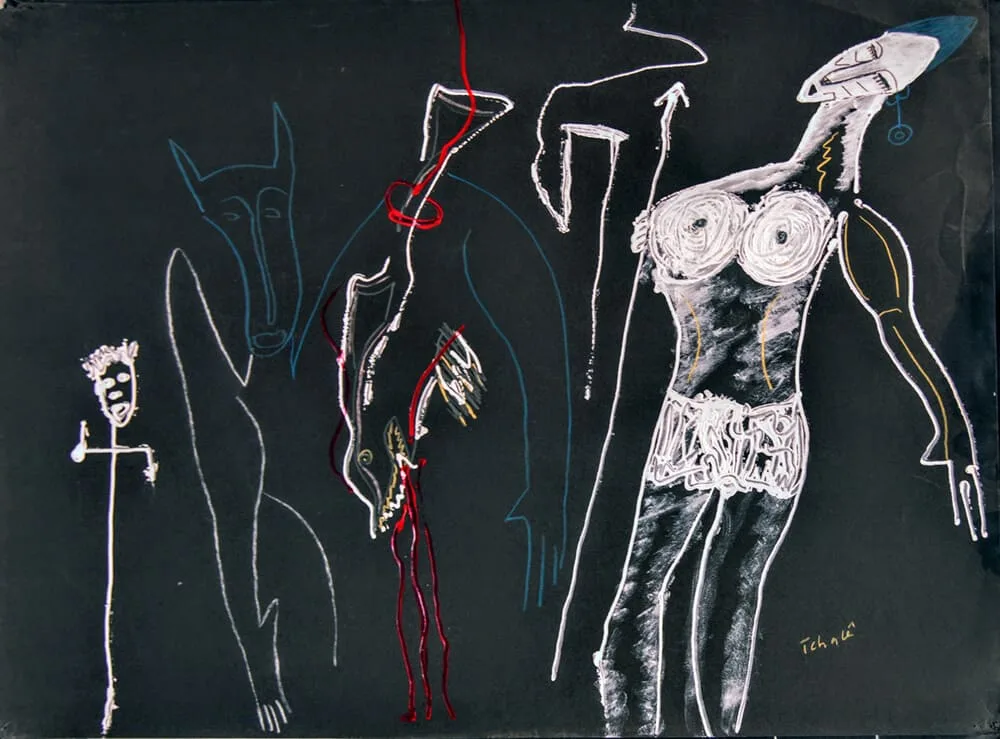

What emerged instead was pure Tchalé: grotesque figures with huge appetites — for food, sex, power, attention. Bodies that took up too much space. Mouths that opened too wide. His palette went electric — yellows that screamed, reds that bled, blues that drowned. His classmates painted careful, abstract pieces or conceptual works. Tchalé painted fat businessmen eating the world. He painted prostitutes as queens and queens as prostitutes. He painted, as he puts it:

“The human comedy, but nobody’s laughing.”

The Swiss were unsure of what to do with him. His work was too figurative for the abstract expressionists, too wild for the traditionalists, too political for the formalists, too funny for the serious artists. But it sold. God knows why, but it sold. Maybe because beneath the carnival colours and distorted bodies, people recognised something true about power, greed, desire — all the things the Swiss pretended they didn’t have.

By 1980, Tchalé was showing in galleries. Small ones at first, the kind that specialised in “emerging international artists.” Then bigger ones. He developed a following among collectors who sought something unique for their white walls. Something that made their guests uncomfortable. Something that made them seem interesting. He could have stayed and built a career as an exotic African artist in Basel. Grown old, painting variations of the same grotesques for the same collectors.

The Return: Choosing Mindelo

Instead, in 1985, he went home.

Cape Verde had been independent for ten years. His brother Manuel had become a national institution, running the craft centre, preserving traditions, and building cultural infrastructure. And Tchalé? Tchalé came back with a Swiss education and a head full of devils. He set up his studio in the family’s old house near the port—not the official port where Manuel had his studio, but the old port, where the fishermen still pulled their boats onto the beach by hand.

The Cape Verde he returned to wasn’t the one he’d left. Independence had brought pride but also poverty. Many of his childhood friends had emigrated to Boston, Lisbon, and Luxembourg. The ones who stayed seemed smaller somehow, worn down by the daily struggle of island life. Mindelo still had its famous carnival, its music, its morabeza (that untranslatable Cape Verdean warmth), but underneath was something more complex. The revolution was over. Now came the tricky part: building a nation from ten scattered islands and a history of slavery and neglect.

Tchalé painted it all. Not the tourist version — the pretty beaches and smiling faces—but the real Mindelo. The drunks sleeping in doorways. The young men with no work and too much time on their hands. The older woman was selling fish with faces like dried leather. The politicians with their big bellies and bigger promises. He painted the “Macho Society,” as he called it — men strutting like roosters while women did the actual work. These weren’t the respectful cultural documents his brother was creating. These were accusations in acrylic.

The Writer Emerges

Painting wasn’t enough. There were things Tchalé needed to say that colours couldn’t capture. So he started writing. First poems, scrawled on the backs of sketches. Then stories. Then novels. The writing was like his painting — excessive, carnival-bright, full of shipwrecks and disasters. His first book, “Todos os Naufrágios do Mundo” (All the Shipwrecks in the World), came out in 1992. The title tells you everything: Tchalé saw disaster everywhere, but made it dance.

More books followed: “Onde os Sentimentos se Encontram” (Where Feelings Meet) in 1998, “O Azul e a Luz” (The Blue and the Light) in 2002, and “Solitário” (Solitary) in 2005: fiction, poetry, something in between. The literary establishment didn’t know what to do with him any more than the art establishment had. His Portuguese was contaminated with Creole, his Creole with Portuguese, both languages influenced by German and French, and English he’d picked up while wandering. He wrote like he painted — too much, too bright, too loud.

But people read him. Especially young Cape Verdeans who recognised their own hybrid existence in his hybrid language. Here was someone who’d been away and come back, who’d learned the coloniser’s forms and bent them into new shapes. His books became cult objects, passed around, quoted, and argued over. He wasn’t just recording Cape Verdean culture; he was inventing it, word by word, paint stroke by paint stroke.

The Studio as Theatre

Visit Tchalé’s studio today — he calls it Ponta D’Praia Atelier — and you enter his universe complete. It’s in an old house that threatens to collapse but never quite does, like Cape Verde itself. The walls are covered with paintings stacked three deep. The floor is a Jackson Pollock of paint drips. The smell hits you: turpentine, oil paint, the sea, something rotting sweetly in the heat.

Tchalé paints standing up, dancing really, moving around canvases that are often bigger than he is. Music plays constantly — Cape Verdean morna, Swiss experimental jazz, Nigerian Afrobeat, whatever catches his mood. He sings along, badly, while he paints. Sometimes he puts down the brush and picks up a guitar. Sometimes he stops everything to write a poem on whatever’s handy — newspaper, cardboard, the wall itself.

The paintings that emerge are explosions. Colours that shouldn’t work together but do. Figures that are simultaneously comic and tragic. A fat politician becomes a balloon about to burst. A prostitute becomes the Virgin Mary, becomes a fish. Everything transforms into everything else. It’s Expressionism, sure, but Expressionism that went to the carnival and never sobered up.

His subjects haven’t changed much over the years: power and its abuses, desire and its frustrations, the comedy of human ambition. But the style keeps evolving. Recent work incorporates found objects — bits of fishing net, sand, pages from Swiss newspapers he saved from the 1970s. The paintings become archaeological sites, layers of time and place. Switzerland and Cape Verde, past and present, all colliding on canvas.

Recognition and Resistance

The international art world eventually caught up with Tchalé. The 2008 Prix Fondation Blanchère at the Dakar Biennial was a watershed — suddenly, curators realised that this wild man from Cape Verde had been doing important work all along. Exhibitions followed: in New York, Paris, Lisbon, and São Paulo. Museums started acquiring his work. Critics wrote serious essays about his “post-colonial aesthetic” and “carnivalesque subversion of power.”

Tchalé reads these essays and laughs.

“They need to complicate everything. I just paint fat men because fat men are funny. And sad. And dangerous. All at once.”

The recognition brought money, which Tchalé spends as quickly as he makes it. Not on himself — he still lives simply, still wears paint-splattered clothes, still drinks cheap wine. However, he funds young artists, buys materials for anyone who asks, and maintains an open-door policy that means his studio is always full of people borrowing supplies, seeking advice, or simply seeking shade.

He opened the Ponta D’Praia gallery in 2014, a space for artists who, like himself, don’t fit neatly into categories. The gallery is as chaotic as his studio — no regular hours, no proper cataloguing system, prices negotiated on the spot based on Tchalé’s mood and the buyer’s attitude. It shouldn’t work, but it does. Young Cape Verdean artists show there before anywhere else. Collectors know to check in when they’re in Mindelo. The space has become what Tchalé always wanted: a place where art happens, not just a place where art is displayed.

The Brother Dynamic

The relationship between Tchalé and Manuel was complex, though neither spoke of it much while Manuel was alive. Fifteen years apart, they were almost different generations. Manuel, the serious older brother who went to Lisbon, married a Portuguese artist and returned to build institutions. Tchalé, the wild, younger brother who wandered Europe, learned from the streets, and came back to tear things down — or at least paint them as they fell apart.

Their studios, just a few streets apart in Mindelo, represented two visions of Cape Verdean art. Manuel’s was ordered, archival, and focused on preservation. Tchalé’s was a scene of chaos, creation, and destruction happening simultaneously. Manuel taught the technique. Tchalé taught irreverence. Manuel worked with the government. Tchalé painted the government with pig faces.

Yet they respected each other deeply. Manuel would bring visitors to Tchalé’s studio, proud of his brother’s success even if he didn’t always understand the work. Tchalé would defend Manuel against younger artists who accused him of being conservative. Tchalé would say:

“He saved our culture, I just play with what he saved.”

When Manuel died in October 2023, Tchalé painted for three days straight. The resulting canvas — ten feet tall, blazing with colour — shows two figures. One ascends toward something bright. The other remains below, still painting. It’s the closest Tchalé has come to sentiment without irony.

The Continuing Circus

At seventy-one, Tchalé shows no signs of slowing. If anything, the work gets wilder. Recent paintings incorporate digital prints, African textiles, and Swiss chocolate wrappers he saved from the 1970s. He’s started a series called “War is Stupid,” which is precisely what it sounds like — powerful idiots destroying things while ordinary people try to survive. The paintings are brutal, funny, and selling faster than he can make them.

He’s writing too. A new novel about a Cape Verdean who becomes president of Switzerland. Poetry that mixes five languages in a single line. Art essays that are really about fish, or essays about fish that are really about art. The literary establishment still doesn’t know what to do with him. He doesn’t care.

Young artists seek him out — not just Cape Verdeans but Europeans, Americans, Africans drawn to his uncompromising vision. He tells them all the same thing:

“Don’t paint what you see. Don’t paint what you think. Paint what you can’t stop yourself from painting.”

It’s terrible advice and perfect advice, which is very Tchalé.

The studio remains open to anyone brave enough to enter. The paintings keep accumulating. The poetry keeps spilling out. The grotesque parade of human appetites continues across his canvases. Collectors complain they can’t get appointments. Tchalé suggests they try fishing instead — the fish are biting, and besides, the ocean is more interesting than art.

Tchalé’s World: Where the Answer is Always Yes

There’s a word in Cape Verdean Creole: morabeza. It embodies warmth, hospitality, and the unique charm of Cape Verdean culture. Tchalé’s work is the opposite of morabeza. It’s acid where morabeza is honey. It’s a confrontation where morabeza is embraced. Yet maybe that’s what Cape Verde needed — someone to paint the shadows that morabeza creates, the things too ugly for hospitality to hide.

His influence on Cape Verdean art is impossible to measure because it’s everywhere. Every young artist who picks up a brush knows they don’t have to paint pretty. Every writer knows they can mix languages, break rules, and make their own grammar. Every creative person knows there’s more than one way home — you can take the direct route like Manuel, or you can wander the world like Tchalé and arrive at the same port, just with more stories.

The international art world continues to try to categorise him. Post-colonial artist? Afro-European? Neo-expressionist? Tchalé ignores the labels and keeps painting. In his studio above the old port, with the Atlantic visible through salt-stained windows, he creates worlds where everything is wrong in exactly the right way. Politicians with pig faces. Prostitutes with halos. Fishermen catching clouds. The human comedy, painted in colours that don’t exist in nature but should.

Ask him what it all means, and he’ll pour you a drink, light a cigarette (he still smokes, despite everyone telling him to stop), and start another painting instead of answering. The painting will be violent and tender, ugly and beautiful, serious and absurd. It will be too much. It will not be enough. It will be precisely what Tchalé Figueira has been doing for fifty years: showing us ourselves, distorted just enough to see clearly.

In the end, that’s what Tchalé represents: the possibility that art doesn’t have to behave. That you can leave home, circle the world, and return with vision scrambled enough to see truth. That a kid from Mindelo can paint Swiss bankers and Cape Verdean fishermen with the same brutal honesty. That exile and return are not opposites but parts of the same journey.

The work continues. The studio door stays open. The paintings accumulate like sediment, layer upon layer of colour and meaning. Tchalé Figueira, at seventy-one, paints like someone just discovering paint—urgent, excessive, necessary. He paints like someone who knows the shipwrecks of the world aren’t metaphors. That’s what happens. The question is: can you make them dance?

In Tchalé’s world, the answer is always yes. Even the disasters dance. Especially the disasters. That’s the joke, the tragedy, and the whole point. In the old port of Mindelo, in a studio that smells of paint and possibility, Tchalé Figueira keeps painting the circus that won’t leave town. We’re all invited. We’re all implicated. We’re all ridiculous.

And somehow, in the riot of colour and form, in the grotesque parade of human appetite, something true emerges. Not beautiful, necessarily. Not comfortable, certainly. But true in the way that only art can be true — by lying with such commitment that the lie becomes more real than reality.

That’s Tchalé’s gift to Cape Verde and the world: the permission to see ourselves as the beautiful disasters we are, and to laugh at the spectacle even as we recognise our own faces in the funhouse mirror of his art.

Bibliography

- “Painting, creating, my personal mythology” Tchalé Figueira, video interview by Marta Lança, edited by Bruno Morais Cabral, translated by Érica Almeida Postiço, World African Artists United, 2023;

- Tchalé Figueira’s profile (gallery), Artsy;

- Masters we need to master: The Cape Verdian brothers, Manuel and Tchalé Figueira, Valerie Kabov, Art Africa;

- Tchalé Figueira Cape Verde, b. 1953, This Is Not A White Cube;

- Virtual Exhibition / Cape Verde / Tchalê Figueira / MORE THAN DESIRE, LOVE, ZO mag’ – magazine d’art contemporain;

- Tchalé Figueira Art for Sale and Sold Prices, Invaluable;

- Tchalé Figueira and Manuel Figueira, Wikipedia;

- Tchalé Figueira, Buala;