Pontão: The Unique, Iconic Pier of Santa Maria

The sun breaks over the Atlantic at 10 a.m. Fishing boats return to Santa Maria. Their hulls paint the water in blues, reds, and yellows. Engines sputter and die as they approach the pier. This daily scene has played out at the Pontão for decades. The wooden pier does more than receive boats. It holds the rhythm of Cape Verdean life.

The Pier in Santa Maria

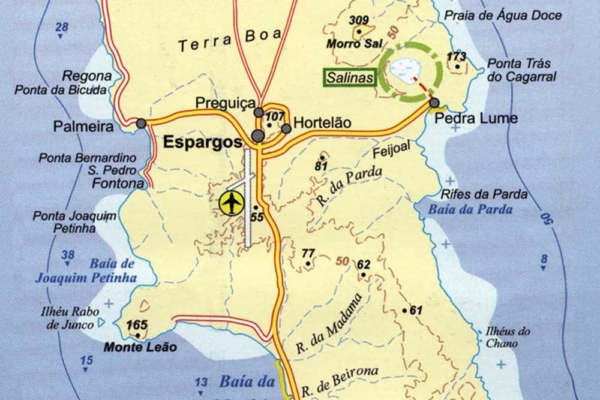

The pier in Santa Maria, known as O Pontão, extends quietly into the Atlantic, a simple wooden structure that has long served as both a working platform and a social meeting point. Originally built to support the salt trade, it now anchors the town’s daily rhythms. In the early hours, small fishing boats dock alongside, and the morning begins with the sound of voices, buckets, and knives at work. Fishermen haul in tuna, wahoo, and other catch, cleaning them on the worn boards while buyers — some local, some from restaurants — make quiet selections. Children gather nearby, some helping, others leaping into the shallow waters with effortless confidence. Later in the day, divers, tour guides, and catamaran crews begin their routines, using the same space to prepare for excursions along the coast.

Destructive Storms

The pier has weathered storms, including significant damage in 2015 and again in 2024, which left it partially unusable for a time. Yet even in disrepair, it remained central to the life of the town. Repairs have allowed fishing and boat tours to resume, though some parts of the original wooden steps are still missing. Still, the pier holds its place — not as a monument, but as part of the everyday. Visitors stop to look out to sea, take photographs, or watch as the day’s catch is brought ashore.

Historical Foundations

Manuel António Martins founded Santa Maria in 1830, when salt drove everything. The white crystals covered the landscape like snow in the tropics, and workers scraped salt from shallow ponds before loading it into carts. These carts rolled on narrow rails directly to the pier.

Years of Great Export

Ships loaded 30,000 tons annually, with most cargo bound for Brazil under Portuguese merchant control. The merchants built warehouses near the shore, establishing Santa Maria for one clear purpose: to export salt. Workers built the first pier at Ponta de Vera Cruz using heavy timber from Portugal. Iron rails connected salt flats to ship holds, and workers pushed loaded carts under the scorching sun before returning with empty ones. This infrastructure created the foundation for what would eventually become today’s Pontão.

The Boom And The End

Brazil killed the trade in 1887 by imposing heavy taxes on imported salt to protect Brazilian producers. Portuguese merchants in Santa Maria watched their market vanish as ships stopped coming and the rails rusted. Workers left for other islands, and Santa Maria crashed hard. Houses emptied, and the pier rotted in the salt air. Only a few fishing families remained, patching the pier with scrap wood to keep it functional for their small boats.

Second Try

The town barely survived this economic catastrophe until 1920, when a Portuguese investor named José Benoliel saw opportunity in the abandoned salt flats. Benoliel brought new equipment and workers, restarting production on a smaller scale. The pier gained new life and ships returned, though fewer than before. The salt business limped along until 1984, when competition from mainland Africa finally ended Cape Verde’s salt era.

The pier outlasted the salt trade by adapting to new purposes. Fishing boats replaced cargo ships, and though the structure shrank, it endured. Tourism followed fishing in the 1960s when Belgian entrepreneurs opened the Morabeza hotel in 1967. Visitors discovered Santa Maria’s beaches, and the pier adapted once again to survive.

Daily Rhythms and Cultural Significance

Locals call it the most touristic site in Santa Maria, and while they’re right, that description misses the deeper point. The Pontão breathes with the town, setting the daily schedule and feeding families while connecting generations. Fishermen leave before dawn in small boats, motoring past the reef. Some head for deep water while others work the coastal shallows, following fish movements learned from their fathers. By mid-morning, they return to a pier that comes alive at 11 a.m.

Fishermen of The Pier

Boats cluster around the wooden posts as fishermen tie up wherever space allows. They haul plastic crates filled with tuna, wahoo, and barracuda onto the planks. Some days bring bonito and dorado, while lucky boats might carry a sailfish. The cleaning starts immediately at the pier’s edge. Sharp knives flash in the sun as fishermen gut their catch, and blood and scales wash into the ocean. Pelicans wait for scraps while cats prowl between the fishermen’s legs, and the smell of fresh fish mingles with salt air. Restaurant owners arrive early because they know which boats catch quality fish.

Negotiations happen in rapid Kriolu with hand gestures at specific fish. Prices depend on size, species, and demand, with cash changing hands based on trust built over the years. No receipts are needed—the day’s menu takes shape right there on the pier. Local women buy fish for family meals, preferring smaller fish that fit their pans. They inspect gills for freshness and press flesh to test firmness, bargaining hard because every escudo matters in household budgets.

Jumpers and Sellers

After school, children dive from the pier’s edge as they’ve done for generations. Their grandparents jumped from these same planks into water that stays warm year-round. Kids compete for the biggest splash while tourists stop to watch, sometimes giving coins for more dives.

Vendors spread handicrafts on blankets along the pier — carved turtles, woven bags, and shell jewellery cover the planks. Artists paint scenes of fishing boats while women braid tourists’ hair in corn rows. Some vendors push too hard for sales, but most smile and wait, knowing patience pays better than pressure.

The Heart of Santa Maria

The 50-meter pier created a compact world where its 12.7-meter width forced interaction. Tourists couldn’t avoid local life, and locals couldn’t ignore tourism. The wooden planks hosted negotiations in Portuguese, Kriolu, English, French, and Italian, with both groups finding balance through daily repetition.

Young men offer fishing trips to tourists, promising big catches and ocean adventures from boats that bob beside the pier. Some deliver on promises while others just motor around the bay, but either way, the dock serves as both a booking office and a departure point.

Economic and Social Hub

Fishermen

Fishing families depend on the Pontão because, without a pier, there is no income. Fathers teach sons to tie knots on these planks where mothers sold fish before the tourists came. Three generations often work on the same boat, maintaining traditions that span decades.

The structure provides everything fishermen need. Boats tie up in sheltered water, and the pier’s height allows easy unloading. Fish cleaning happens immediately, with buyers waiting steps away. Ice vendors deliver directly to boats — everything is centred on this wooden platform.

At low tide, boat maintenance happens beneath the pier. Fishermen scrape hulls and patch holes with fibreglass before painting over repairs. The pier’s shade provides relief from the sun as tools pass between boats, and everyone helps during emergency repairs.

Sellers

Handicraft vendors established a secondary economy, arriving after the fish sales ended. Established sellers replaced blankets with wooden stalls where they sell jewellery made from fish bones and bags woven from recycled fishing nets. They paint scenes of the pier itself, and tourist euros supplement fishing income—one good day can equal a week of fishing.

The pier economy spreads inland through interconnected businesses. Fish cleaners sell scraps for animal feed while ice factories deliver before dawn. Mechanics fix outboard motors on the beach, and woodworkers repair damaged boats. Gas stations extend credit to fishermen, with each business connecting to the wooden structure extending into the sea.

Restaurants and Bars

LobStar restaurant capitalised on a perfect location by building at the pier’s entrance. Diners watch fishermen while eating their catch, with fresh fish travelling just twenty meters from boat to plate. The view stretches eight kilometres along Santa Maria beach, and on clear days, Boa Vista island floats on the horizon 40kilometress away.

Other businesses followed LobStar’s model as bars opened with pier views and tour operators set up booking stands. Dive shops stored equipment nearby, creating an economic zone around the Pontão. Property values increased with proximity to the pier, demonstrating its role as a financial anchor.

Natural Beauty and Tourist Appeal

Engineers chose the spot for practical reasons — deep water allowed boat access, rocky bottom provided a solid foundation, and currents prevented sand buildup. The beauty came as an unexpected bonus. The pier offered front-row seats to nature’s daily show. Water shifted from navy to turquoise with the tide while morning light turned waves gold and sunset painted the ocean red. The beach curved toward Praia de Algodoeiro in a perfect arc where white sand met blue water for seven kilometres.

Marine Life

Marine life performed daily beneath the pier. Dolphins surfaced near the posts at dawn, hunting schools of sardines. Fishermen considered dolphins good luck and never interfered with their hunt. Schools of jack fish flashed silver beneath the surface while barracuda patrolled the pier’s shadow. Rays glided through the shallows, and sea turtles occasionally made appearances.

Popular Touristic Spot

Tourists came for the beaches but remembered the pier because the structure provided a focal point for photos. Every Santa Maria postcard featured the Pontão with its wooden planks leading eyes toward the horizon. Colourful boats added movement while morning fish sales provided authentic action that couldn’t be staged.

Travel writers took notice, ranking Santa Maria among Africa’s best beaches. But their articles always mentioned the pier because it separated Santa Maria from anonymous resort beaches. The Pontão meant real life happened here, and journalists loved the contrast between luxury hotels and working fishermen sharing the same beach.

Social media amplified the pier’s fame as Instagram filled with sunrise shots from the Pontão. TikTok videos featured kids diving into crystal water while travel bloggers posted fish market scenes. The wooden pier became Santa Maria’s signature image that hotels used in marketing and tour packages, promising an “authentic pier experience.”

Meeting Place

The pier also worked as a social space where locals gathered in the evening shade. Older men played cards on upturned crates while teenagers flirted by the railings. Families brought picnics on Sundays because the Pontão belonged to everyone.

Destruction and Resilience

October 11, 2024 arrived with violence that meteorologists had warned about. The tropical wave generated swells unlike anything in recent memory, with waves reaching heights that old fishermen called unprecedented. But warnings don’t stop the ocean. The Atlantic attacked at high tide with swells crashing over the pier deck. Water surged between the planks as support posts groaned under lateral pressure. The pier had survived storms before, but this felt different to everyone watching.

The end section failed first when witnesses heard cracking wood above the wave roar. The deck tilted seaward and posts snapped like matchsticks. The outer 20 meters vanished in seconds, becoming wooden debris tumbling in the foam.

Photos and Recordings

Videos captured the collapse on mobile phones that recorded the disaster. The images spread across WhatsApp within minutes and Facebook filled with shaky footage. The outer section had vanished in brown water, leaving forward pillars standing alone like cemetery markers. Social media spread the images globally within hours.

Destruction of the Pier

The storm raged for two days with each high tide bringing new damage. More planking tore loose and handrails disappeared. The fish cleaning stations washed away completely. When seas finally calmed, only the concrete base remained intact with about 30 meters of pier surviving from the original 50. Locals mourned like they’d lost family members. Fishermen stood on the beach staring at wreckage while children asked when they could dive again. Vendors lost their selling spots and restaurant owners worried about fish supply.

Tourists who’d visited days before expressed shock online, with one British visitor writing: “We were so sad. It was magical just last week.”

Economic Impact

The economic impact hit immediately as boats couldn’t unload efficiently. Fish sales moved to the beach where sand contaminated the catch and prices increased. Some fishermen traveled to Palmeira port instead, but the twenty-kilometer trip cost fuel money that small operators couldn’t afford.

The Pier Renovation Plans

The timing stung everyone because August 2024 had brought hope. The Tourism Ministry had announced renovation plans with 400 million escudos allocated. Engineers had surveyed the structure and contracts were being prepared. The storm turned renovation into total reconstruction. Cape Verde’s president visited Santa Maria to walk the damaged shoreline and speak with fishermen. He promised rapid rebuilding while the Tourism Minister accompanied him. They announced emergency measures for temporary facilities to help fishermen, promising reconstruction would start soon.

Future Phoenix

The government moved fast using plans that already existed from the August announcement. The World Bank had guaranteed 480,000 euros, and officials decided to build better rather than just rebuild. The storm created opportunity from disaster.

The Pier Reconstruction Plans

Engineers presented ambitious designs for a new pier stretching 120 meters into the ocean. This more than doubles the original length, allowing boats to tie up in deeper water where storm waves will have less impact. The width increases to 14 meters, providing more space for more activities.

Construction will use modern materials with concrete pillars replacing wooden posts. These pillars sink deep into bedrock with steel reinforcement to resist lateral forces. The deck uses treated hardwood over steel beams designed to last fifty years, compared to the original pier’s forty years of patches.

Design details show careful thought throughout the structure. Shade structures protect fish cleaners from sun using roofs with traditional palm frond styling but modern materials for durability. Benches let visitors rest while watching activities, with placement allowing ocean views without blocking work areas.

Dedicated Space to Sit and Enjoy

A café occupies the mid-pier section — nothing fancy, just coffee, beer, and snacks. Tables overlook the fishing boat anchorage, and the structure includes storage for chairs during storms. Proper toilets replace the inadequate facilities with men’s and women’s rooms meeting international standards. Disabled access ramps comply with modern regulations.

Modern Solutions

Technical systems support fishing operations through an electric winch that helps boats unload heavy catches. The system runs on solar power while LED lights allow night fishing preparation. Security cameras protect against theft and free WiFi helps fishermen check weather reports.

In Honour of the Fishermen

A new square connects the pier to town in a space that honors fishing heritage. A statue depicts traditional boat building while plaques remember notable fishermen. Trees provide shade for gatherings in a design that integrates the Pontão into Santa Maria’s urban fabric. It becomes public space, not just infrastructure.

Contracting the new Pier Construction

April 2025 brought contractor selection with Chinese and Portuguese companies bidding. A joint venture won with a budget reaching 10 million dollars. This includes two support boats for construction — semi-rigid inflatables that will ferry materials and serve rescue duty after construction.

Construction requires moving current users to assigned spots at temporary facilities. The government built basic cleaning stations near Praia Antonio Sousa while vendors got spaces at the municipal market. Everyone wants the old location back because temporary means hardship.

New Requirements for Protection of Turtle Nesting Areas

Environmental reviews added important requirements. Turtle nesting areas need protection, so construction must pause during breeding season. Silt barriers prevent reef damage while marine biologists monitor water quality. The pier helps tourism but can’t harm nature.

Enduring Legacy

The Pontão tells Cape Verde’s story in wood and concrete. Salt trade birthed it, fishing sustained it, and tourism transformed it. Each era left marks on the structure — scars from mooring ropes, stains from fish blood, and smooth spots where children’s feet polished wood over generations. The pier witnessed Santa Maria’s complete evolution. It saw sailing ships yield to motor vessels and watched thatch houses become concrete hotels. It felt the first tourist’s tentative steps and absorbed millions of footfalls since. Each person added to its accumulated story.

Untamed Power of The Ocean

Nature reminded everyone who controls the ocean when the Atlantic gave and took without sentiment. Cape Verdeans understand this relationship — they name winds, read wave patterns, and respect the sea’s power. But they also rebuild, adapt, and endure.

Sadness of Missing the Pier

Santa Maria waits for its new pier with a town that feels incomplete. Fishermen miss their routines and the beach lacks its focal point. Children ask parents when they can dive again while tourist photos seem empty without colorful boats clustering around wooden posts. Some worried the new pier would lose authenticity because concrete and steel don’t age like wood. Modern materials might lack soul, but the plans show sensitivity. The design respects all users by giving fishermen better facilities and tourists improved amenities while locals gain community space. Balance remains the central goal.

The reconstruction represents faith in the future. Ten million dollars says Santa Maria matters to Cape Verde and the world. The 120-meter length anticipates growth while improved facilities expect more visitors. But fishing stays central—the pier serves working boats first with tourism following fishing, not the reverse.

Together For a Better Future

Traditional boat builders share knowledge during construction delays. Master craftsmen teach young men on the beach near the damaged pier. They shape hardwood with hand tools to build boats that will launch from the new pier. Skills pass between generations because the Pontão’s destruction created unexpected teaching time. Local artists document the transition as painters capture the broken pier’s drama. Photographers record construction progress while musicians compose morna songs about loss and renewal. The disaster becomes cultural memory preserved through art.

The Pontão represents connection at every level. Land meets sea at its planks while tradition meets modernity in its reconstruction. Local meets global in daily encounters that define Cape Verde—a small nation between continents, an archipelago bridging worlds. A wooden pier captures this unique position.

Faith and Persistence

When complete, the new Pontão will host familiar scenes. Dawn will bring departing fishing boats and mid-morning means returning catches. Negotiations will echo in Kriolu while children dive from new railings. Tourists will photograph the authentic chaos as life flows across the planks again.

The pier embodies persistence in a town that survived salt trade collapse and weathered economic isolation. Santa Maria embraced tourism without losing identity, and the October storm tested this resilience again. The response proved Cape Verde’s strength—they mourn losses, clear debris, and build better.

The Meaning

Some structures matter beyond their function. The Pontão de Santa Maria holds memories, sustains families, and defines place. Its destruction brought sadness while its reconstruction brings hope. The new pier will rise from the Atlantic, and Santa Maria’s heart will beat at the water’s edge. Some things endure because communities will them to exist, and the Pontão is one of these essential things.