The Weight of Sodade: Good Understanding of the Emotion

Eleventh Island: the Meaning of Sodade

The guitar knows the way home better than the man who plays it. Armando Tito’s fingers find the familiar frets without needing to look. Sixty years of muscle memory guide them through another morna in his apartment in Lisbon. Outside, the usual chaos plays its big-city chords. Tuk-tuks are hauling tourists. Fado comes out of the restaurant speakers. Fresh laundry is flapping on balconies. But here, surrounded by sun-bleached photographs of São Vicente’s mountains and that impossible blue Atlantic, there’s only the sound of strings and a voice that left Cape Verde forty years ago but never quite arrived anywhere else.

“I carry Cape Verde with me,” he says, not looking up from his guitar. “Always missing it. Always.”

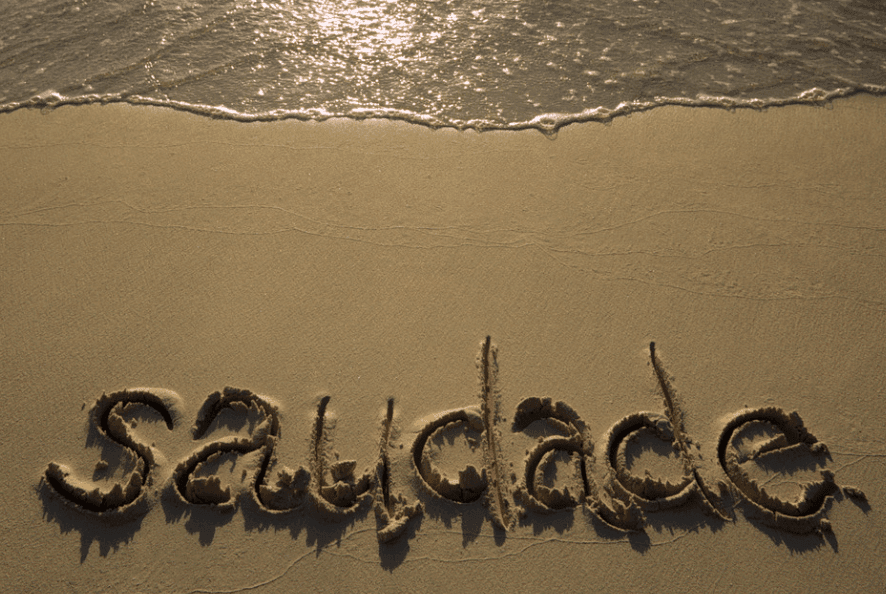

He’s singing about sodade — that Cape Verdean word that sits like a stone in the chest, too heavy to swallow, too essential to remove. Not nostalgia exactly. Not quite longing. More like love that persists through absence, or absence that becomes a form of love. Try to translate it and you’ll fail. Try to escape it, and you’ll fail harder.

The math of Cape Verde is brutal: 550,000 people live on the islands, with at least a million more scattered elsewhere. New Bedford. Boston. Lisbon. Paris. Rotterdam. Dakar. Each carrying their portion of sodade like a genetic inheritance, passing it to children who might speak broken Creole or none at all, but still wake sometimes with that ache for islands they’ve never seen.

“We say Cape Verde has eleven islands,” the singer Mayra Andrade once explained. “Ten you can find on a map. The eleventh is everywhere else — the diaspora.”

The Architecture of Absence

Born from Departure

Picture this: ten volcanic islands and eight islets flung across the Atlantic like God’s careless handful of stones, 350 miles west of Senegal. When Portuguese sailors stumbled upon them in 1460, they found no people, barely any water, soil so poor that even today, less than two per cent can grow food. The Sahel’s rain shadow falls across these rocks. Drought comes like clockwork. Famine follows.

From the start, Cape Verde meant leaving. First, the enslaved Africans, dragged from the mainland to these islands, were stacked in stone barracoons before the Atlantic crossing. Then their descendants, fleeing hunger, signing onto whaling ships, scattering like seeds that might grow better anywhere but home. Each departure carved sodade deeper sense of sodade into the culture, until it became not just a feeling but a way of being.

The word comes from the Portuguese saudade, which is untranslatable, derived from the Latin solitudo, meaning solitude. But Portuguese saudade has a certain softness, a romantic ache. Cape Verdean sodade cuts sharper. It tastes of salt and departure, of mothers watching the harbour, of letters that take months to arrive if they arrive at all.

“Sodade isn’t about missing,” Teófilo Chantre tells me from his Paris apartment, another exile in another European city. “It’s about the structure of Cape Verdean life. To survive, we leave. To return, we must first go. This isn’t poetry. It’s economics.”

The Mathematics of Migration

The numbers tell their own brutal story. The 1940s drought: 30,000 dead, nearly a quarter of the population. Between 1900 and 1970, 80,000 Cape Verdeans shipped as “contract labour” to São Tomé’s plantations — slavery by another name. The whaling ships that stopped for water and salt took men who wouldn’t return for years, if ever.

New Bedford alone absorbed thousands. By 1860, Cape Verdean hands worked the harpoons, Cape Verdean backs bent over try pots, and Cape Verdean widows waited for ships that had already sunk. Today, Brockton, Massachusetts, has a 16% Cape Verdean population. The old whaling port has more people from Fogo and Brava than some actual villages on those islands.

Money flows backwards across the Atlantic — remittances comprising 12% of Cape Verde’s GDP. Bidons arrive from Boston stuffed with clothes, medicine, and dollars. Care packages as physical manifestations of sodade, love converted to material goods and shipped home.

But sodade predates these migration patterns. Those 13th-century troubadours who sang of soidade weren’t anticipating whaling ships or colonial labour contracts. They were already mapping the territory of loss, the homeland that exists more perfectly in memory than it ever did in life.

The Poet of Exile

Eugénio Tavares and the Codification of Loss

Brava Island, 1867: Eugénio Tavares arrives in a world already shaped by departure. The smallest inhabited island breeds the biggest dreams of elsewhere. By twelve, he’s publishing poetry. By his twenties, his newspaper columns attacking Portuguese rule had made him dangerous. The colonial administration offers a choice that isn’t a choice: silence or exile.

Tavares chooses exile, but on his terms. Ten years in New Bedford, where he founded Alvorada — the first Portuguese-language newspaper in America. Think about that: a poet from a tiny African island, creating a voice for his people from a Massachusetts fishing town. The circles of diaspora are spinning inside each other like nautilus shells.

In New Bedford’s cold winters, Tavares writes the mornas that will define sodade for generations. “Hora di Bai” — Time to Leave. “Força di Cretcheu” — Force of Yearning. These aren’t just songs about missing home. They’re instructions for how to miss, how to carry absence without letting it destroy you.

“Corpo cativo bá bo qu’é escrabo,” he writes. “Captive body, go, you are slave / Oh living soul, who will carry you?” The split between body and soul — one forced to wander for survival, the other forever anchored to those volcanic rocks. This is sodade’s essential duality: you leave but never depart, arrive but never land.

When Tavares finally returns to Brava in 1910, he brings American ideas about independence, about rights, about resistance. Sodade becomes political. Under colonialism, Cape Verdeans are doubly exiled—from Africa by water, from themselves by Portuguese rule. The emotion becomes a form of quiet rebellion, a way to remain Cape Verdean despite centuries of being told you’re Portuguese subjects.

The Mindelo Renaissance

Fast-forward to the 1940s in Mindelo, São Vicente Island. The port thrums with British ships in need of coal, American vessels hunting whales, and everyone in need of supplies. Francisco Xavier da Cruz—B.Léza to anyone who matters — grows up watching the harbour, his parents serving British merchants who treat Mindelo like their personal gas station.

At the height of the empire, Mindelo was one of the world’s busiest coaling stations. Ships from everywhere drop anchor here. B.Léza absorbs it all — Brazilian sambas from sailors, jazz from American merchant marines, fado from Portuguese administrators. He takes these influences and creates something entirely Cape Verdean: the “Brazilian half-tone,” passing chords that make morna swing and cry simultaneously.

But B.Léza’s real innovation is thematic. Where Tavares wrote about exile, B.Léza writes about the ocean itself —that vast blue antagonist that both isolates and connects. “Mar Azul,” his masterpiece, doesn’t plead with fate or God but with the water itself: “Oh sea, stay calm / Let me go see my country again / Kiss my mother.”

The ocean as metaphor becomes the ocean as character. Not just geography but destiny. The thing that brought slaves, that takes sons, that delivers letters and corpses with equal indifference.

B.Léza dies young in 1958, but his harmonies live on. Every Cape Verdean guitarist knows his chord progressions, the way they turn like ships tacking against the wind, never quite arriving at resolution.

The Barefoot Diva’s Global Stage

Cesária Évora and the Universalization of Sodade

For forty years, sodade has remained Cape Verde’s secret. The world doesn’t know what it’s missing. Then comes Cesária Évora, and everything changes.

Picture her: Mindelo, 1960s, singing in sailors’ bars for drinks and cigarettes. Voice like aged grogue, rough and smooth simultaneously. She performs barefoot — solidarity with the poor, she says, but really it’s deeper than that. Shoes are for people going somewhere. Cesária has already arrived at the only place that matters: inside the song.

Life beats her down. Failed marriages. Children to feed. Portuguese colonialism is giving way to independence that doesn’t pay any better. By 1970, she quits singing. Ten years of silence. Sodade without even music to carry it.

Then, in 1985, a Cape Verdean musician in Lisbon convinces her to record. She’s 44, thinking life is mostly over. Instead, it’s just beginning. She moves to Paris — another exile joining centuries of exiles. Records trickle out. French critics notice. Portuguese audiences remember.

Then, “Miss Perfumado” drops in 1992, and the world discovers what Cape Verdeans have always known. The album’s centrepiece is “Sodade,” written in the 1950s by Armando Zeferino Soares, a song that asks over and over: “Ken mostra-bo es kaminhu longe?” — Who showed you this faraway road?

The Paradox of Success

Here’s what’s beautiful and terrible: Évora sings sodade so perfectly that audiences who speak no Creole understand completely. Tokyo. New York. Berlin. Tears in languages that have no word for what they’re feeling.

“I saw Japanese audiences crying,” Armando Tito remembers from the tours. “They didn’t understand the words, but they understood. Cesária didn’t just sing sodade. She was sodade. The absence was in her voice.”

But success creates its own exile. The more famous Évora becomes, the less she’s home. She spends the 1990s and 2000s circling the globe, singing about an island she rarely sees. The woman who embodies Cape Verde for millions exists mostly elsewhere. Even sodade has sodade.

When she died in 2011, her house in Mindelo remained open — according to Cape Verdean tradition, allowing the spirit to find its way out. But also symbolic: the door that never closes, the departure that never ends, the return that never quite happens.

The Mechanics of Memory

How Sodade Works

Forget what you think you know about nostalgia. Sodade operates by different rules.

- Personal sodade: missing specific faces, particular streets, the way light falls on Fogo’s volcano at sunset.

- Collective sodade: the shared ache of a scattered people, a nation that exists more in longing than in land.

- Anticipatory sodade: mourning losses that haven’t happened yet but will — the cousin who’s definitely leaving, the grandmother who won’t last another winter, the islands themselves shrinking under rising seas.

“Sodade is honest,” Maria Santos explains. She’s a psychologist in Boston, treating Cape Verdean immigrants for forty years. “It doesn’t pretend Cape Verde is paradise. We know why we left — the drought, the poverty, the impossibility of it all. But knowing why doesn’t make the leaving hurt less.”

This honesty distinguishes sodade from simple nostalgia. No one romanticises the famine years, the colonial oppression, the ships that never returned. The ache comes not from wanting to return to an idealised past but from accepting that even an imperfect home, once lost, leaves permanent absence.

The Second Generation’s Burden

Michael Fernandes was born in New Bedford in 1987. His parents left Santiago in the seventies. He’s been to Cape Verde exactly twice — once for a funeral, once for a wedding. He speaks kitchen Creole, the kind you use with grandmothers but not in public.

“I have sodade for a place I don’t really know,” he says. “It’s in the food my mother cooks, the music at family parties, the stories that start with ‘back home.’ I’m homesick for someone else’s home.”

This inherited sodade might be harder than the original. At least first-generation immigrants have real memories. Their children carry ghosts of ghosts, shadows of islands they know mainly through photographs and folklore.

Yet the emotion persists, sometimes stronger in the second generation than in the first. They know they’re between worlds — too American for Cape Verde, too Cape Verdean for America. Sodade becomes their inheritance, their burden, their connection to something larger than suburban Massachusetts life.

The New Sodade

Digital Connections, Persistent Distances

WhatsApp changed everything and nothing.

Now Ana Silva in Boston talks to her grandmother in Santiago every day. Video calls for birthdays. Live streams of village festivals. The digital bridge that previous generations couldn’t imagine. Yet the distance remains, maybe feels worse for being so visible. João Monteiro, 25, engineering student, packing for Lisbon:

“My parents left, and that was it,” Ana says. “Letters at Christmas, maybe a phone call if someone died. Now I see my cousins’ kids growing up on Instagram, and I watch my neighbourhood changing on Google Earth. I’m connected but not there. It’s almost worse.”

Digital sodade: seeing your sister’s wedding on Facebook Live, watching Carnival through someone’s phone, experiencing home through screens. The technology that was supposed to eliminate distance instead makes it visible, quantifiable, and undeniable.

Climate Change and Future Sodade

The new math is terrifying. The ocean rise could swallow whole villages. Drought cycles are intensifying. The young don’t talk about when they’ll leave, but when they will.

“We’re the last generation to know Cape Verde as it was. My kids will visit a different country. I have sodade for what they’ll never see, for what doesn’t exist yet but already doesn’t exist.”

This pre-emptive sodade, grieving for losses not yet realised, might be the cruellest form. At least traditional sodade mourns what was. This new variant laments what might have been, what should have been, what won’t be.

Scientists project that by 2100, Cape Verde could be largely uninhabitable. The entire nation might become a diaspora; the islands would just be rocks in the ocean again. Sadly, the only thing proving people ever lived there at all is sodade.

The Universality of the Specific

Why Sodade Matters Beyond Cape Verde

Every immigrant knows this feeling, even if they don’t have the word for it. The Welsh call it hiraeth. Romanians say dor. Russians have toska. But sodade seems closest to the bone, because Cape Verdeans had to name it to survive it.

“Cape Verdeans gave the world a gift,” says Fernando Arenas, who teaches Lusophone studies at Michigan. “They named what millions feel. In an age of mass migration, climate refugees, and digital nomads, we all know sodade. We just didn’t know what to call it.”

The pandemic made everyone taste it — separated from loved ones, unable to travel, experiencing life through screens. Suddenly, the whole world was Cape Verdean, scattered and aching for connection.

The Music of What Remains

Back in Lisbon, Armando Tito sets down his guitar. The last note hangs between us like a question nobody’s asking. He pours two glasses of grogue. We drink to the distances that can’t be closed.

“You want to know what sodade means?” He laughs, but it’s not a laughing matter. “It means love becomes absence and absence becomes love. Same thing for us. We exist in the space between.”

He picks up the guitar again. Another morna, older than both of us, newer than tomorrow’s departure. The music says what words can’t: that some distances are permanent, some returns are impossible, some forms of love exist only in their absence.

The Presence of Absence

An Emotion for Our Times

There’s no cure for sodade. Cape Verdeans don’t “get over it” any more than they get over having hands or speaking Creole. It’s not a problem that requires a solution, but a reality that requires a witness.

The Cape Verdean flag features ten stars, representing the ten islands of Cape Verde. But maybe there should be an eleventh — not solid but outlined, an absence against the blue. The star of sodade, the island that exists everywhere and nowhere, populated by everyone who carries home in their hearts instead of beneath their feet.

As the world heats up and seas rise, families scatter across borders, the connection becomes increasingly indirect, digital, and the distance remains physical. We can see that sodade slowly transforms from a Cape Verdean word to everyone’s reality. It teaches that some losses are permanent, some distances unbridgeable, some loves exist only in absence, and life continues anyway. Not despite the ache but through it, because of it.

“Ken mostra-bo es kaminhu longe?” The question echoes still. Who showed you this faraway road?

History. Hunger. The sea itself.

But the question isn’t seeking an answer. It’s a lament dressed as inquiry, a way of saying: Here we are, scattered but whole, absent but present, gone but never leaving.

This is sodade’s final teaching: that even the deepest losses become beautiful when shared, that absence itself is a form of presence, that a people scattered by history remain connected through the simple act of missing each other, together, across whatever distance the world demands.

The music continues. In New Bedford living rooms, Lisbon apartments, Paris cafés and Praia nightclubs. Each note is a thread in the web that connects every Cape Verdean heart to every other, creating from scattered islands an archipelago of emotion that no distance can dissolve.

Sodade might be untranslatable not because it’s uniquely Cape Verdean but because it’s so essentially human that no single language could contain it. Cape Verdeans simply had the courage — or the necessity — to name it, to sing it, to transform unbearable absence into enduring art.

The guitar knows the way home. The hands that play it might wander. Might cross oceans and decades. Might forget everything but this. That some forms of love are stronger than geography. That some connections transcend presence. That home isn’t always a place you can return to, but sometimes just the ache that proves you came from somewhere. That you belong to something. That you are never truly alone in your absence. Because millions share it with you, each carrying their portion of sodade like a compass that doesn’t point north but inward, toward that eleventh island where all the departed gather. Where all the music plays at once. Where sodade finally means not loss but finding. Finding each other in the shared weight of what’s gone.

Bibliography

- A Social History and Concept Map Analysis on Sodade in Cabo Verdean Morna, Aoki, K., Academia.edu, 2020.

- Militant Nostalgia in Cape Verdean Literature, Matthew Teorey, Global Journal of Human-Social Science;

- A Sodade: An Emotional Journey Between Nostalgia and Perfumes. Agua de Cabo Verde;

- Sodade, Cesária Évora, Saudade on Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia;

- The Story of Morna: Cape Verde’s Music of Displacement and Return, BUALA, 26 May 2021.