Salt Flats of Santa Maria: Beautiful Mosaic in Sand

In the south of Sal Island, beyond Santa Maria’s golden beaches and resort hotels, lies a different kind of treasure – a broad, sunbaked expanse of inland salt flats.

These salinas stretch out just north of Santa Maria town, their pale crust shimmering under the Saharan breeze. They are often overlooked in favour of Sal’s more famous crater salt lake at Pedra de Lume. But Santa Maria’s salt pans have a story all their own. It was here that the town of Santa Maria was born in 1830, founded expressly to harvest the “white gold” of salt.

Today, the salt flats are quiet and mostly dry, visited occasionally by wading birds and curious tourists. However, they remain a poignant landscape – a protected site of ecological interest and a living monument to the island’s history. This article explores how these inland salt flats once fueled Santa Maria’s early growth. What has become of them since the salt trade ebbed. And how the local community regards the salinas today.

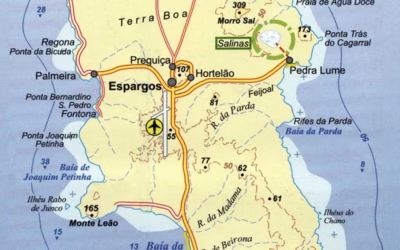

Google Maps: Salina

Coordinates: 16.61119838° N, -22.902441436° W

Salt Production and the Founding of Santa Maria

In the 19th century, salt was as good as currency for the Cape Verde islands, and Sal Island owes its very name and early prosperity to this commodity. The natural salt pans near Santa Maria were developed around 1830 under the direction of Manuel António Martins, a Portuguese trader who envisioned turning Sal into a salt-exporting hub. To build the evaporation ponds, enslaved labourers were brought from West Africa. They dug away sand and soil to expose the impermeable bedrock, upon which a grid of shallow salt pans was laid out. Ingenious wooden windmill pumps (constructed by skilled enslaved artisans) drew brine from beneath the ground. They channelled it into the pans, while an iron rail tramway was installed to carry the crystallised salt to the seashore.

By the mid-1800s, Santa Maria had become a booming salt-production village, exporting up to 30,000 tons of salt per year at its peak. A wooden pier built at Ponta de Vera Cruz served as the loading point where mound after mound of coarse sea salt was ferried onto ships bound for the Americas and beyond.

Rise and Fall of Sal’s Salt Wealth

Most of Santa Maria’s salt in those days was destined for Brazil, where it preserved cod fish and meat in the tropics. This transatlantic trade flourished until 1887, when Brazil imposed steep tariffs on imported salt to protect its producers. The impact on Sal was devastating. Santa Maria lost its primary customer, and the salt business began to decline rapidly. Many local workers left the island in search of work and better situations. The once-bustling salt village slipped into poverty. In the early 20th century, there were attempts to revive and modernise the operation.

In 1903, Santa Maria’s remaining salt producers partnered with a French company to form the Société Salines de Sal (SSS), even building a processing factory equipped with advanced machinery to enhance salt quality by removing excess magnesium. Nevertheless, that venture went bankrupt just a few years later in 1907. A subsequent arrangement with a German company around 1914 also failed, prompting another wave of emigration from Sal as jobs evaporated.

The Second Try

It was not until the 1920s that Santa Maria’s salinas got a second wind. In 1920, a Portuguese enterprise (Companhia do Fomento) purchased most of the salt flats and invested in their rehabilitation. By 1927, they had secured a lucrative new export market in the Belgian Congo and were shipping Cape Verdean salt to West Africa. This revival of the salt trade breathed new life into Santa Maria. The village, which had been languishing, began to grow again – residents built sturdier houses, laid out streets, and the local economy found its footing. Through the mid-20th century, salt remained a pillar of Santa Maria’s livelihood alongside a small tuna fishing and canning industry. Older inhabitants still remember the white salt mountains glistening in the sun and the steady flow of work in the pans.

However, history repeated itself: global changes after the 1960s made Sal’s salt less competitive. The Belgian Congo gained independence (ending that export market by 1961), and Cabo Verde itself became independent in 1975. With rising costs and no reliable buyers, the Sal salt industry slowly unravelled. By 1984, routine maintenance of the Santa Maria salinas had ceased, and the remaining infrastructure was in a state of decay. The great salt flats of Santa Maria, once the economic engine of the island, were finally abandoned to the elements in the late 20th century.

A Protected Landscape: The Salt Flats Today

Piles of harvested salt rest on the evaporation ponds of Santa Maria’s inland salinas, a sight that hints at the small-scale extraction still carried out by locals today. Although this 69-hectare area remains in a good state of conservation, it is no longer commercially exploited, except for occasional artisanal use. In 2016, the Cape Verdean government officially designated the Santa Maria salt pans as a Protected Landscape, recognising their historical and cultural importance and ensuring the site is safeguarded from development. The flats are encircled by the larger Costa da Fragata nature reserve, which protects the coastal dunes and beaches just east of Santa Maria. Any construction on the salt flats is prohibited by law, preserving the open panorama of pale pools and saline crusts as far as the eye can see.

Visiting Salt Flats

Walking onto the salt flats today, one finds a patchwork of shallow basins divided by low earthen ridges. The ground crunches underfoot, covered in a brittle frosting of salt crystals. In the dry season, the pans are mostly bone-white and empty, but after rare rains or high tides, they transform into mirror-like lagoons reflecting the broad African sky. Algae thriving in the hyper-saline mud can tinge some pools pinkish, and along the edges, hardy salt-tolerant plants (such as Suaeda shrubs and glasswort) poke through the cracked soil. The salinas also provide an unexpected haven for wildlife on this arid island. Wading birds visit to feed on brine flies and crustaceans in the shallows – recent birdwatchers have recorded black-winged stilts picking their way across the pans, along with sandpipers, plovers, and other migratory shorebirds stopping over on their trans-Atlantic journeys. Amid the quiet, one can occasionally spot an alguidar (plastic bucket) or a coarse brush left behind – simple tools of local salt-gatherers who still come to rake up a small amount of salt by hand, much as their forebears did generations ago.

Footprints of the Salt Trade

Virtually none of the heavy infrastructure from Santa Maria’s salt boom remains in operation. The clacking windmill pumps that once drew up brine have long fallen silent, and the iron rails that carried wagonloads of salt are now rusted away or buried under sand. A few concrete foundations and weathered wooden beams at the periphery of the flats hint at former storehouses and machinery, but they stand empty, slowly eroding in the salt air. In Santa Maria town, however, the legacy of the salt era is still visible.

The old pier – originally built in the 1800s for loading salt ships – endures as a central landmark. Every day, fishermen on the Santa Maria Pier haul in the catch and locals gather to buy fish or to dive into the turquoise water, likely unaware that this same pier was once piled high with blocks of salt bound for Brazil. The salt trade has vanished. However, its footprint lies etched into Santa Maria’s landscape, geography and cultural memory. The protected salinas themselves, shimmering under the tropical sun, are now a landscape of ruins and resilience: a natural salt marsh reclaiming a piece of industrial heritage.

Heritage, Tourism, and Local Perspectives

The inland salinas are a source of nostalgia for many Cape Verdeans. They take pride in the knowledge that their town “started with white gold.” The salt flats are still frequently mentioned in local guides’ stories and many Cape Verdean songs. They are reminders of a time when Santa Maria was not just a tourist enclave. In recent years, there have been efforts to honour this heritage. The government’s protection of the site was motivated not only by ecological concerns but also by a will to preserve the historical and cultural value of the salinas for future generations. There is even talk about potential new uses: the mineral-rich mud and dense brine of the ponds could be used for therapeutic baths and wellness tourism, similar to the spa-like experience at Pedra de Lume’s salt crater. So far, such ideas remain speculative, but they reflect an understanding that the salinas are an asset – a place where history, nature, and community identity intersect.

Salt Flats Nowadays

Salt flats serve a relatively modest and intermittent use. Some local entrepreneurs and families have continued to harvest salt on a small scale. They are selling bags of it locally as gourmet sea salt and souvenirs. This grassroots extraction is conducted with respect for the landscape, posing minimal threat to the environment. However, it has not been without controversy.

In 2018, a dispute erupted when a private tourism developer, the Oásis hotel group, claimed ownership of the lands of the Santa Maria salinas – lands that had once belonged to the long-defunct “Fomento” salt company. Several local salt-gathering cooperatives, which had been operating with official licenses since 2013, found themselves suddenly barred from the site by the company’s guards. The Oásis group argued that it had purchased the old company’s property rights and reportedly went so far as to post signs warning that the area was private. The local salt workers pushed back, doubting the legality of the claim – after all, the salinas are state heritage and part of a protected landscape. “For over 20 years, we have extracted salt here, and no one ever objected. Only now this group appears, saying they own it,” one cooperative leader, Adilson Almada, told reporters in frustration.

The controversy was a wake-up call for the community, which rallied to insist that the salt flats must remain accessible and managed for the public good. As of this writing, the issue has been brought to the attention of the authorities, and any development plans have been stalled pending clarification of ownership and the site’s protected status.

Salt Flats and Tourism

Meanwhile, tourism in Santa Maria has largely moved on to other attractions – the beaches, windsurfing spots, and the surreal float-in-the-water experience at Pedra de Lume. By comparison, Santa Maria’s inland salinas receive only a trickle of visitors. Still, those tourists who do venture here often come away moved by the stark beauty and historical aura of the place.

The salt flats are usually included as a brief stop on Sal Island day tours led by local guides: a bumpy 4×4 drive off the main road brings visitors to the edge of the pans. Guides will explain how the sun and wind evaporate the salty groundwater, leaving glittering crusts of pure salt just as in centuries past. You will not find crowds – one travel blogger who visited likened the scene to seeing famous salt flats elsewhere, “without all the tourists”. In the quiet, you might only encounter a solitary woman balancing a basket of freshly raked salt on her head, or perhaps a couple of birdwatchers scanning for stilts in the shallow pools.

There are no visitor facilities beyond maybe a signpost, and entry is free. As such, the salinas feel refreshingly authentic: an open-air museum of nature and history, uncommercialized and oddly serene. Some tourists wish for more on-site interpretation, but others appreciate the lack of overt tourism and find that the place speaks for itself.

Visiting Salinas Today

Standing on the Santa Maria salt flats at sunset – the town’s rooftops glowing on one horizon, dunes and kite-surfers on the other – it is easy to sense the layers of meaning embedded in this landscape. Here is where Santa Maria began, forged from salt and sweat; where generations of Cape Verdeans laboured and where global currents of trade once converged. Today, the salinas are returning to a more natural state, frequented by egrets and plovers rather than slave labourers or factory workers.

Nevertheless, they continue to serve the community in subtle ways: as a buffer against urban sprawl, a salt marsh habitat, a link to cultural memory, and a humble tourist attraction that connects visitors with the island’s soul. In a town now defined by vibrant music nights and holiday resorts, the inland salt flats remain austere and timeless. They remind everyone that Sal Island’s story – and even its very name – was written in salt. Santa Maria’s salinas, though quiet now, still exude the atmosphere of history and perseverance, ensuring that the legacy of the island’s salt era will not be forgotten.

Bibliography

-

- Almeida, Ray. A History of Ilha do Sal—University of Massachusetts Dartmouth (archived);

- Resolução nº 36/2016 – Estratégia e Plano Nacional de Negócios das Áreas Protegidas, Cabo Verde;

- Salinas de Santa Maria – Paisagem Protegida. Caboverde-Info (in Portuguese);

- “Salinas no Sal: Grupo Oásis comprou todo o património da antiga companhia ‘Fomento’.” A Nação newspaper (5 Sept 2018);

- Phil and Garth Travel Blog – “10 Best Things To Do on Sal, Cape Verde” (Apr 28, 2024);

- BirdForum – “Sal, Cape Verde, April 2018” discussion.