Cape Verdean Dogs: from Caravels to Creole Companions

Uninhabited Islands Awaiting Companions

When Portuguese mariners first set foot on the Cape Verde archipelago in the mid-15th century, they encountered islands devoid of human habitation or large mammals. The islands – including Sal – had almost no indigenous people and no native land mammals whatsoever. This isolation meant that all domestic animals, dogs included, arrived only with the advent of human colonisation. Cape Verde thus offers a unique case study of how animal introductions accompanied colonial settlement.

The Portuguese discovered the islands around 1456 and began permanent settlement in 1462. From that moment, ships didn’t just carry people, but an entourage of Old World livestock and pets. Early chroniclers describe the new colony almost like a blank slate – a “place of arrivals” for flora and fauna transplanted from Europe and Africa. No wild dogs or other beasts roamed Cape Verde’s shores until people brought them. In essence, the story of dogs on these islands begins with the Age of Exploration.

First Paws on Shore: Dogs Land with the Portuguese

Historical and archaeological evidence indicates that domestic dogs first arrived in Cape Verde with Portuguese sailors and settlers in the 15th and 16th centuries. During the era of Atlantic exploration, Portuguese ships routinely carried domesticated animals – not only livestock like goats and pigs, but “probably dogs” as well. Dogs were valued shipboard animals, often serving practical roles. Notably, Portuguese vessels carried small Portuguese Podengo hounds on their caravels to serve as rat-catchers and hunting dogs.

Contemporary sources suggest that many of Cape Verde’s earliest dogs were descendants of Portuguese Podengo dogs brought on ships, where they helped keep rat populations down. These hardy little hounds – fast, agile, with prick ears and sand-colored coats – would go on to seed the canine population in the new colony. In short, the first dogs on Cape Verde likely arrived as part of the Portuguese toolkit for survival and settlement, stowed in caravel holds alongside human colonists, goats, chickens, and seeds.

Many Cape Verdean dogs today have the prick ears, size, and coat colours reminiscent of their Portuguese Podengo ancestors.

Once ashore, dogs took on essential functions in the fledgling colonies. Portuguese settlers used dogs for guarding settlements and aiding in hunts, much as they did back home. Early towns like Ribeira Grande (Cidade Velha) on Santiago, founded in 1462 as the first capital, likely kept dogs as guards to protect storehouses and homes. The presence of valuable trade goods and enslaved labour meant security was paramount, and contemporaneous accounts often mention guard dogs protecting properties (for example, a 1590s report from Santiago describes dogs barking at night as a deterrent to thieves, as noted in colonial letters).

On farms and estates, dogs would have been used to hunt feral livestock (such as wild goats or pigs that quickly multiplied) and to control pest animals. Although direct written records from the 1500s rarely single out dogs, their ubiquity is implied – by 1580, Cape Verdean settlements were sufficiently developed that European visitors noticed the settlers’ “many dogs” living among them, indicating that dogs had firmly established a presence across the islands.

Carried by Settlers, Not by Slaves – But With African Influence

Were dogs brought by enslaved Africans, or by others, rather than the Portuguese? The historical consensus is that dogs were introduced primarily by Portuguese colonists, not by enslaved people. Enslaved Africans, who were tragically brought to Cape Verde as part of the transatlantic slave trade, were not in a position to carry animals with them. Slave ships were brutally overcrowded and focused on human cargo. Thus, it was Portuguese ship captains and settlers who deliberately transported dogs (and other domestic animals) to the islands.

That said, the influence of Africa on Cape Verde’s dogs should not be discounted. Cape Verde quickly became a creole society of mixed Portuguese and West African origin. Enslaved Africans and free Afro-Portuguese inhabitants would have interacted with the dogs introduced by Europeans. Over time, African traditions and attitudes toward dogs blended into local culture, potentially affecting breeding and dog-keeping practices. For example, many West African societies valued dogs as village guards and hunting companions, and those cultural views likely carried over.

It is possible that some African dogs reached Cape Verde later through informal means (for instance, West African traders or freedmen moving to the islands might have brought a local dog along). However, no firm record documents an early African-imported dog. Genetic research may eventually clarify this point. Preliminary genomic studies of Cape Verdean strays aim to trace their ancestry and have begun comparing island dogs’ DNA with that of Portuguese and Brazilian dogs (which themselves have European and African lineage).

The working hypothesis is that Cape Verde dogs’ gene pool is predominantly Iberian (Portuguese), with possible minor inputs from African village dogs via the archipelago’s African residents. In short, the Portuguese seeded the dog population, but the dogs then became part of the Afro-Portuguese community, shaped by both European and African hands over centuries.

Island-Hopping: How Dogs Spread Through the Archipelago

After their initial arrival on Santiago, dogs gradually spread to the other islands of Cape Verde along with human migration. Each island’s settlement history provides clues to when dogs likely first appeared there:

Santiago (São Tiago)

Settled in 1462, it was the first island with an established town (Ribeira Grande). Dogs arrived here first, accompanying the founding Portuguese families and soldiers. By the late 1400s, Santiago had a sizable population of colonists (and slaves), and references to their livestock imply dogs were present to help manage cattle and guard property.

Fogo

Colonised by the 1480s, Fogo’s rugged terrain was used for ranching. The Portuguese likely brought dogs to Fogo to help hunt goats and wild cattle on the volcano’s slopes. Indeed, archaeological excavations at early Fogo homesteads have unearthed bones of cattle, goats, and pigs – all animals that require herding or guarding, tasks suited to dogs. It’s reasonable to assume that by the 16th century, Fogo had its share of dogs working alongside settlers.

Brava

Inhabited by the 16th century (some accounts say after a 1680 volcanic eruption on Fogo, many moved to Brava). Dogs would have come with those settlers as well, by translocation or natural increase. Brava’s small size and isolation likely limited canine numbers initially, but by the 1700s, dogs were noted in its villages (Brava was a source of crew for New England whaling ships, whose logs mention island dogs occasionally begging at docks by the 1800s).

São Nicolau, Santo Antão, Boa Vista, Maio

These islands developed more slowly (São Nicolau and Santo Antão saw settlers by the mid-16th century; Boa Vista and Maio were first used as pasture lands and for salt collection in the 16th–17th centuries). As each island gained a permanent population, dogs were introduced as part of the colonial “package” of animals. For example, goats and sheep were intentionally released on Boa Vista and Maio to breed for supplies, and dogs would have been brought soon after to assist settlers in managing those animals. By the 1700s, travellers’ accounts describe packs of semi-feral dogs in the more sparsely populated islands – evidence that canine populations had become self-sustaining, spreading wherever humans lived.

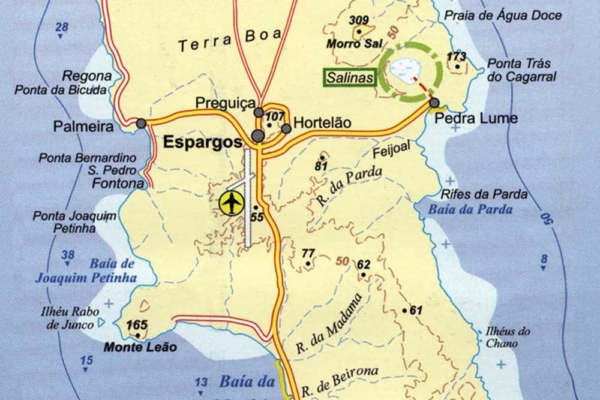

Sal Island

Sal is a special case. For the first three centuries after its 1460 discovery, Sal remained largely uninhabited. Apart from the odd ship landing or a tiny fishing camp, there were few humans – and thus likely no resident dogs – on Sal for a long time. This changed around the late 18th century, when Sal’s salt deposits began to be commercially exploited. Salt works at Pedra de Lume, and later Santa Maria drew workers and settlers from other islands (and from Portugal). With these newcomers came their dogs.

We can fairly pinpoint Sal’s first significant presence of dogs to the late 1700s and early 1800s, corresponding to the establishment of a permanent community during the salt boom. A small fishing village existed by 1720, so a handful of dogs may have been there earlier, but Sal truly “went to the dogs” once its salt industry took off.

By 1830, the town of Santa Maria had been founded as a salt-export hub, and contemporary reports mention European merchants keeping guard dogs at the salt warehouses (to prevent theft of the “white gold”). Sal’s case illustrates that no island remained dog-free once humans settled – dogs spread archipelago-wide, but their timing mirrored each island’s colonisation timeline.

Uninhabited Islets

The only places without dogs were the uninhabited islets like Santa Luzia, Branco, and Raso (which had no fresh water or villages). Historical ecological surveys note no feral dogs on those islets – unlike feral goats or cats, which sometimes did establish. Dogs, dependent on human support or larger territories, did not colonise truly deserted islands. They remained tied to human communities.

Thus, by around 1800, domestic dogs were present on all nine inhabited Cape Verde islands. They often travelled inter-island by boat with their owners. For instance, officials moving from Santiago to become governors on other islands would bring along their household, including pet dogs. Likewise, inter-island trade ships sometimes ferried dogs as gifts or goods – there are accounts from the 19th century of sailors in Mindelo (São Vicente) trading puppies in port. Over generations, these movements blended the gene pools, so that today’s Cabo Verdean dogs form a loose landrace found across the archipelago.

Faithful Servants and Feral Scavengers: Dogs in Colonial Life

In the colonial era, dogs carved out diverse roles in Cape Verdean settlements. Guard dogs were highly prized in towns and estates. Portuguese colonists, wary of pirate raids and internal revolts, kept dogs to alert them and defend them. For example, in 1712, when French pirate Jacques Cassard attacked Ribeira Grande, chroniclers noted that watchdogs barked furiously as the alarm was raised, underscoring their presence as sentinels in the community.

Dogs also likely served to track down runaway enslaved people in some cases – a practice common in other colonies – though specific records in Cape Verde are scarce. We do know that colonial authorities elsewhere used “cães de fila” (catch dogs) to hunt fugitives; given Cape Verde’s smaller scale, this may have been rare but not impossible.

More benignly, dogs were companions and helpers. On plantations (fazendas) in Santiago’s interior, hunting dogs were used to catch wild game. While Cape Verde had no native game animals, rabbits were introduced (perhaps accidentally) and became pests; landowners with packs of dogs would organise rabbit hunts to protect gardens. Wild goats in the highlands were another target – agile podengo-type dogs could chase them down for meat.

The dogs’ utility extended to pest control in settlements as well. Rats and mice, arriving with ships, threatened stored food; alongside cats, terrier-like dogs were turned loose in warehouses at night to kill rodents. A 1790 letter from a British trader on Boa Vista even remarked that the “little dogs here are better mousers than our cats”, indicating how ingrained their pest control role was.

Not all colonial attitudes toward dogs were positive, however. As in many colonies, stray or feral dogs sometimes multiplied, causing concern. Periodic droughts and famine – harsh realities of Cape Verde – led to human hardship and, consequently, to the neglect of animals.

By the 18th century, one can find references in Portuguese administrative correspondence to “exterminate roaming dogs” during famine years, presumably because starving strays were seen as scavengers or threats to livestock. For instance, an 1833 ordinance in Praia (Santiago) ordered the culling of unowned dogs after a rabies scare (rabies was a feared disease, and without modern medicine, the only prevention was to reduce stray populations). Such measures indicate that Cape Verde’s dog population was large enough to warrant public attention.

On a more everyday level, dogs were part of the social fabric of villages and towns. Letters and travel diaries from the 19th century paint charming vignettes of island life with dogs underfoot: pups playing in church yards, mongrels trotting behind fishermen, and old “guard dogs” napping at the feet of traders in the shade of acacia trees. American whaling ships that harboured at Brava and São Vicente in the 1800s often took note of the friendly local dogs that greeted sailors on the docks, looking for scraps. Charles Darwin himself, when the Beagle stopped at Santiago in 1832, observed the presence of domestic animals in Porto Praya – including “several dogs lounging in the heat” – as a sign of the established colony (though he was more focused on geology than dogs).

By the early 20th century, accounts suggest that Cape Verdean dogs had stratified into two populations: the cared-for village dogs that belonged to families, and a semi-feral fringe of strays living off garbage. This dynamic likely existed earlier as well. Most Cape Verde dogs lived a semi-wild existence – free-roaming by day, loosely attached to households that fed them occasionally. Travellers noted that many homes did not consider their dogs to be fully pets in the European sense. Dogs were often left to fend for themselves for food, resulting in a population of scrawny street scavengers. An 1880s Portuguese report from São Vicente described “dozens of ownerless dogs haunting the port’s beach, living off fish offal and following any stranger with a morsel”.

At the same time, some wealthier families kept purebred dogs imported from Europe (for example, by the late 19th century, a few British merchants in Mindelo had brought mastiffs and bulldogs). These imports, however, were few – the average Cabo Verdean dog remained of local stock, adaptively evolved to the climate and conditions.

Despite occasional official efforts to control them, dogs proved resilient in Cape Verde’s harsh environment. They became lean, tough survivors – much like the human population that endured cycles of drought. It’s telling that in Cabo Verdean Creole, the common word for a mutt or stray dog is “catchoro” (from Portuguese cachorro), and folk sayings use dogs to symbolise tenacity and loyalty. Dogs, whether valued or neglected, were simply part of everyday colonial life – guarding by night, foraging by day, and even providing comfort. There are touching anecdotes: one eighteenth-century ship captain recounted how a Cape Verdean dog on Fogo refused to leave its master’s graveside, a testament to canine loyalty that transcends time and place.

Digging Up the Past: Archaeological Clues

What do the archaeological records show about early dogs in Cape Verde? Given that dogs were not native, one might expect colonial-era dig sites to yield canine remains if dogs lived and died alongside people. So far, archaeological studies in Cape Verde have found abundant evidence of introduced livestock (bones of cattle, goats, pigs, etc.) but very few explicit dog remains. For example, at the recently excavated early settlement of Alcatrazes on Santiago (occupied in the late 1400s–1500s), researchers uncovered animal bones from the settlers’ diet – notably cow, goat, and pig – yet reported no identifiable dog bones in the assemblage. This absence could mean several things. Dogs were likely not eaten (unlike livestock, they wouldn’t appear in food refuse), and if a dog died, it might not be tossed in a rubbish pit where archaeologists dig. Colonists may have buried dogs separately, or the remains have not been recognised in digs yet. Thus, the lack of dog bones is not evidence of a lack of dogs, but rather the particularities of archaeological visibility.

One intriguing archaeological clue comes not from bones but from the settlement layout: at Cidade Velha (Ribeira Grande), excavations uncovered small structures and courtyards in the 16th-century town that may have been kennels or pens for animals like dogs. Also, historical maps of Ribeira Grande show “casa de cão” (dog house) labelled in the backyard of the Governor’s residence, indicating that officials kept trained dogs on the premises. So while a dog skeleton in Cape Verdean soil remains elusive, indirect evidence (documents, site features) confirms their presence.

Interestingly, no ancient dog burials or ceremonial dog remains have been documented in Cape Verde – unlike some cultures where dogs were buried with honours. The settlers, being Christian Europeans, did not typically bury dogs in consecrated ground or with ritual, and enslaved Africans did not have the opportunity to create lasting monuments. As a result, the archaeological footprint of dogs is subtle. If one day, zooarchaeologists sifting through colonial garbage dumps in Santiago or São Nicolau do find a dog skull or tooth, it will be a significant first. But even without it, we have a convergence of other evidence – written records, genetic data, and the known patterns of colonisation – that leaves little doubt: dogs were indeed part of Cape Verde’s earliest colonial settlements.

European Bloodlines and African Ties: Genetic Heritage of Cabo Verde’s Dogs

What breeds or genetic stock did Cape Verde’s dogs come from, and how have they evolved? The consensus is that the archipelago’s dogs derive mainly from Iberian (Portuguese) breeds, with possible admixture from African canines over time. As mentioned, the Portuguese Podengo (Pequeno and Médio) – a primitive hunting hound – is thought to be a major progenitor of Cape Verde’s mongrels. These dogs were common on Portuguese ships and would have been readily left in the new colonies. The physical appearance of many Cape Verdean dogs today indeed resembles that of Podengos: they are medium- to small-sized, with short coats, pointed muzzles, and erect ears. Many are tan or sandy in colour. This suggests a founder effect from those early ship dogs. A Cape Verdean street dog lounging in Sal’s dunes could easily be mistaken for a Podengo wandering a village in Portugal – a living link to the Old World.

Over the centuries, natural selection and island conditions shaped the dogs. Only the hardiest survived cycles of drought and scarcity, likely reinforcing traits like small size (to require less food) and agility (to scavenge and hunt lizards or rodents). The result is a population of so-called “Creole dogs” – not a formal breed, but a landrace adapted to Cape Verde. They are analogous to the “Indian pariah dog” or other feral dog populations in warm climates. Despite this adaptation, their genetic roots still point back to Europe. In fact, ongoing genetic studies by veterinary researchers are examining Cape Verde’s stray dogs at the DNA level for the first time. Early findings (from a project launched in 2023) show that these dogs carry genetic haplotypes common in Southern European dogs, reinforcing the idea that they descend from stock introduced by Europeans. The research, which compares Cape Verde dogs’ genomes with those of Portuguese village dogs and Brazilian dogs, hopes to unravel any African input as well. Since Brazil’s dog populations historically also stemmed from Portuguese colonisation (with some contribution from African dogs via the slave trade in the Americas), finding similarities between Cape Verdean and Brazilian strays could illuminate those shared pathways.

What about identifiable breeds? Aside from the Podengo type, Cape Verde’s dogs likely drew from a mix of European breeds present in the 15th–18th centuries. These could include Iberian mastiff or sheepdog breeds (used for herding livestock brought to the islands) and Portuguese water dogs, which were popular among sailors for working around boats. It’s conceivable that a Portuguese water dog or two came to Cape Verde on fishing vessels – the breed was known to assist fishermen and could have been used in coastal settlements to retrieve fish or guard boats. If so, some Cape Verdean dogs with shaggy coats or partial webbing in their paws might hint at that lineage. However, no distinct local breeds were ever formally developed on the islands. The dogs remained a melting pot, interbreeding freely.

One strong piece of evidence for the European origin of Cape Verde’s dogs comes from disease genetics. A 2021 study of the canine transmissible venereal tumour (CTVT – a cancer that spreads among dogs) identified a case in Cape Verde and traced the tumour’s DNA lineage. The results showed that it belonged to a clade common in Europe and the Americas. In simpler terms, the disease strain in a Cape Verdean dog matched those found in dogs of European descent, not an isolated African lineage. This again aligns with the notion that Europeans imported the dogs’ forebears.

Though genetics tells a predominantly European story, the African influence might be cultural and indirect. West African dog breeds (such as the Basenji-like pariah dogs of the Sahel or the larger village dogs of Guinea) could have been introduced if traders from the African coast brought dogs to sell, or if Cape Verdean settlers obtained dogs during voyages to Guinea. Cape Verde was a hub in the slave trade network, and sometimes animals were part of that exchange. For instance, historical records show that in the 18th century, Guinean merchants gifted Cape Verdean governors exotic animals, such as parrots, and occasionally “a fine hunting dog” from the mainland as tokens of goodwill. Such an African dog, if bred on the islands, could introduce new genes. While this was likely rare, it is a tantalising possibility that Cape Verde’s canine gene pool has a dash of West African flavour.

In summary, the genetic legacy of Cape Verde’s dogs is largely that of the hardy southern European mutt, shaped by centuries of natural selection under tropical conditions. They form part of the wider family of “Atlantic world” dogs that followed the routes of colonisation – cousins to the street dogs of Brazil, the Caribbean “potcakes”, and other New World dogs with Old World roots. As scientific techniques advance, we will undoubtedly learn more, but even now, Cape Verde’s mongrels embody a living history of voyages, colonists, and creolization in the Atlantic.

Dogs in Cabo Verdean Folklore and Culture

Despite their ubiquitous presence, dogs in Cape Verde were not exalted in myth or featured prominently in oral lore as they were in some other cultures – likely because they were an introduced species already familiar to both Portuguese and African settlers. However, over time, Cape Verdeans wove dogs into their proverbs, folklore, and everyday language. The archipelago’s culture drew on both Portuguese and West African traditions, and we can see reflections of canine themes from both sides:

European Folklore Influence

Portuguese folklore includes tales of wolves and enchanted dogs (for example, the Iberian werewolf legends, or the belief that the seventh son becomes a lubisomem – werewolf – chased by dogs).

In Cape Verde, one of the popular folktale cycles features “Ti Lobo” (Uncle Wolf) and Chibinho, which is essentially a trickster tale adapted to the local setting. In these stories, Ti Lobo – a wolf or wild dog character – is outwitted by a smaller animal (often a clever goat or hare). This directly mirrors Portuguese and European fables of cunning foxes and foolish wolves, transplanted into Creole culture. The use of a wolf/dog as a character shows how European imagery persisted.

Yet, over generations, Cape Verdeans made the tales their own, sometimes casting Ti Lobo as just a big stray dog lurking around the village. These stories served as moral lessons about greed or gullibility and would be told to children in Creole. Thus, while there isn’t a creation myth about dogs, the animal did enter the folk narrative repertoire as a stock character.

African Beliefs

Many enslaved Africans in Cape Verde’s early years were from Senegambia and Upper Guinea, regions where dogs were common but not typically worshipped (in contrast to, say, ancient Egypt’s jackal-headed gods). Still, African proverbs and beliefs about dogs travelled with them. For instance, an old Mandinga proverb says, “If you do not step on a dog’s tail, it will not bite you,” meaning if you don’t provoke trouble, you won’t be hurt – a saying that found its equivalent in Cabo Verdean Creole usage.

In some African spiritual traditions, dogs are viewed as guardians at the village threshold, keeping away evil spirits and witches. Echoes of this may be seen in Cape Verdean superstition: even up to the 20th century, some islanders held the belief that when a dog howls at night, it portends a spiritual presence or impending death – a belief common in parts of Africa and Europe alike. This kind of omen lore likely merged both heritages.

Local Legends

Cape Verde has its share of local legends, though few centre on animals. One exception is the spooky tale of the Fantasma da Pedra (“Ghost of the Stone”) on Sal Island – the spirit of a slave who died in the salt flats and purportedly appears at night. In some retellings, this ghost is accompanied by a spectral black dog, an image perhaps inspired by European folklore of ghostly black dogs. It shows how dogs even slipped into ghost stories, symbolising death or the underworld (reminiscent of the Cerberus myth or the Black Shuck of English lore).

Meanwhile, some islands have place-names referencing dogs: e.g., “Baía dos Cães” (Bay of Dogs) on São Nicolau, allegedly named after a pack of wild dogs seen by sailors on the shore. These toponyms hint that dogs were notable enough to earn geographic distinction.

Proverbs and Language

The Cape Verdean Creole language uses dogs in idioms, as many languages do. To say “he’s as faithful as a dog” is a compliment, whereas “life of a stray dog” denotes a rough, marginal existence. A common Creole admonition to a troublemaker is “Ka mexe ku kanidu dormi” – “Don’t disturb a sleeping dog” – basically identical to the English “let sleeping dogs lie.” Such phrases demonstrate the integration of dogs into people’s conceptual world.

Dogs also became part of Creole music and songs metaphorically; for example, an old funaná (folk song) from Santiago uses a dog’s loyalty as an allegory for a lover’s loyalty, showing even in the arts that the animal is a point of reference.

Social Attitudes

Over time, attitudes towards dogs in Cape Verde ranged from affectionate to pragmatic. There is evidence of oral traditions that discouraged cruelty to animals, including dogs – a value possibly stemming from both African empathy towards domestic animals and Portuguese Catholic teaching on kindness to all of God’s creatures. On the other hand, chronic poverty meant that dogs were low on the priority list; the Creole phrase “katxor d’ rua” (street dog) became a metaphor for someone with no support or home, indicating a somewhat pitiful view of strays.

In rural areas, dogs were sometimes semi-sacred guardians; for instance, on Fogo, farmers traditionally believed that a good dog could sense an oncoming volcanic eruption and alert villagers. While not a religious myth, it underscores the trust placed in dogs’ instincts.

In summary, Cape Verdean oral and cultural traditions portray dogs as familiar members of society rather than divine or mythical beings. They appear in tales as tricksters or companions, in sayings as symbols of loyalty or warning, and in superstitions as omens or guardians. This aligns with the islands’ history – the dog was an introduced helper and friend, not an object of cult or deep mythology. The real “myth” of dogs in Cape Verde is how they, alongside people, adapted to a new land and became part of the collective story.

A Continuing Tail ( Tale 🙂 )

From the moment Portuguese caravels first anchored off these once-empty islands, dogs have been a constant if humble part of Cape Verde’s unfolding history. They arrived as early stowaways and working animals aboard European ships. They guarded the first colonial homes and hunted in the first plantations. They spread with settlers to every isle of the archipelago, even the barren Sal, once humans ventured there. They mixed and evolved into the scrappy cão crioulo (Creole dog), unique to Cape Verde – a mixture of Old World breeds moulded by the African sun and island survival. Through colonial prosperity and peril – the heyday of the slave trade, pirate attacks, droughts and famines – dogs remained by the colonists’ and common folk’s side, sometimes loved, sometimes neglected, but always present.

Scientific research continues to shine new light on this journey. Archaeologists are excavating early settlements, uncovering clues about how colonisation affected the environment and which animals were present. Geneticists are sequencing the DNA of today’s stray dogs in Cape Verde to map their ancestry and health, finding links that span oceans. These studies not only tell us about dogs, but also about human history, since wherever people go, their animal companions follow. In Cape Verde’s case, the dogs are a living legacy of its colonisation by Europe and its peopling by Africans, an integral thread in the creole tapestry of the islands.

Even today, the sight of a dozing dog in the shade of a tamarind tree in Praia or a pack trotting along Santa Maria’s beach in Sal is a direct continuation of centuries of island life. Modern Cape Verde faces challenges with stray dog overpopulation – an issue rooted in those early patterns of semi-wild dogs – and local animal welfare groups now work to humanely manage and care for the “forgotten dogs of Sal” and beyond. In their efforts, one can see echoes of the long relationship between Cabo Verdeans and their dogs: a mix of compassion, practicality, and resilience.

From the past, when dogs guarded colonial outposts, to the present, when they greet tourists on sunny beaches, Cape Verde’s dogs embody a history of voyages, adaptation, and cultural fusion. They may not have monastic pedigrees or epic legends written about them, but their story enriches our understanding of how humans and animals together shape new worlds. As popular-science writer Enio Pereira quipped:

“If the walls of Cidade Velha could talk, they’d tell of barking in the night.”

In those barks echo the historical origins we’ve explored: when and how the first dogs came to Sal and its sister islands, who brought them, how they spread, what roles they played, and how people regarded them. It’s a fascinating saga – truly a tail of the islands – and it continues to this day, as every new litter of puppies in Cape Verde carries a bit of that blended heritage forward.

Read also: Stray Dogs of Sal Island: Their Past and Situation Now

Bibliography & Sources:

- Exploring genomics and immunity of the Cape Verde stray dogs, Pires, A. E., et al., Revista Lusófona de Ciência e Medicina Veterinária, 18 (Special Issue), pp. 67–74, 2025;

- Excavating Alcatrazes, Santiago Island, Cape Verde: early colonial impacts on land, people and material culture, Evans, C., Sørensen, M. L. S., et al., Antiquity, 99(408): e63, 2025, via Cambridge University Press;

- The People of the Cape Verde Islands: Exploitation and Emigration, Carreira, António, New York: Africana Publishing, 1982, ISBN: 9780208019882;

- Notes on introduced mammals in Cabo Verde, Hazevoet & Masseti, Zoologia Caboverdiana 2: 25–30, 2011;

- On some remains of dog (Canis familiaris) from the Mesolithic shell-middens of Muge, Portugal, Detry, C. & Cardoso, J., Journal of Archaeological Science 37(11): 2762–2774, 2010, via ResearchGate;

- A Nação Cabo-Verdiana: Entre Ser e Estar, Correia e Silva, António, Praia: Instituto da Biblioteca Nacional, 2002;

- Cartas de Cabo Verde, Fernandes, José, Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional (1888);

- CREOLEs – Genomics and Immunity of Cape Verde Stray Dogs, Pires, A.E.; Róis, A.; Vendas, J.; Blaschikoff, Ludmilla; Palma, H.; Pires, I.; Catita, J.; et al., 3º Encontro do laboratório Associado AL4animalS, 2024;

- Folklore Thread – Cabo Verde, r/FolkloreAndMythology, Reddit, 2023;

- Cape Verde History – The Voice For The Forgotten Dogs Of Sal, Cape Verde;

- A History of Ilha do Sal, Instituto Nacional de Estatística (Ray Almeida, ed.), 2016.